It’s not unusual for a large natural history museum, such as The Field Museum of Chicago, Illinois, to display taxidermy mounts of African lions. What is unusual, though, is that the two male lions that have been featured at the museum for decades are both mane-less...and both man-eaters.

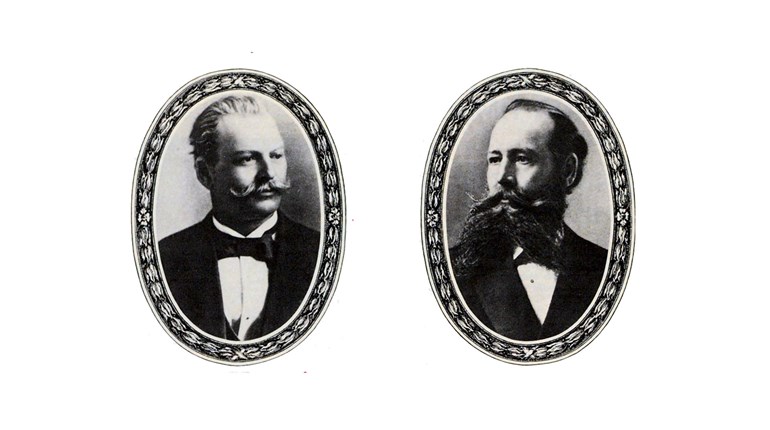

The story behind the two lions began in March 1898 in East Africa, a region of the "Dark Continent" that would one day become Kenya. The British had begun building a railroad bridge over the Tsavo (pronounced SAH-vo; the “T” is silent) River, employing some 3,000 native Africans and Indian Hindus. In charge of the project was Chief Engineer Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson (1865-1947).

No sooner had the construction project begun than a pair of male lions began attacking the workers at night, slipping into their tents and dragging victims off screaming into the darkness. The lions would then eat their human prey. Having few or no firearms, the workers were essentially helpless.

They first tried keeping the lions away by maintaining campfires throughout the night and building "bomas," large thorn-brush fences, around their camps. But nothing discouraged the aggressive lions. The animals grew so bold that they either jumped the bomas or slithered through on their bellies. As a result, hundreds of workers fled the railroad project fearing for their lives, and construction eventually ground to a halt.

In typical British fashion, Colonel Patterson took it upon himself to rectify the problem. At first he tried luring the lions into a trap set inside an empty railroad boxcar, but the animals were too wary for that. He knew then that the only way the man-eaters could be stopped would be by shooting them. He also knew the dangerous work of hunting the animals would have to be done on the big cats’ terms—at night—as the lions went into hiding during the day.

Patterson spent several nights sitting on a platform-style tree stand before shooting the first lion on December 9, 1898. In his written account, he states that he wounded the lion with one bullet from a high-caliber rifle, the shot hitting the lion in the back leg, but it escaped. When the cat returned the next night and began stalking Patterson, he shot it through the shoulder, penetrating the heart. The animal was found lying dead the next morning, not far from Patterson’s tree stand. The big cat measured 9 feet, 8 inches from nose to tip of tail; it took eight men to carry the carcass back to camp.

Twenty days later (December 29, 1898), Patterson shot and killed the second Tsavo lion. One source stated that he fired as many as nine shots into the cat to bring it down. His first round was fired from atop a scaffold built near recent goat kills made by the lion; two more rounds were fired into the lion 11 days later. When Patterson located the wounded lion the day after that, he shot it three more times, crippling it severely. He then finished it off with three additional rounds, shooting it twice in the chest and once in the head. Patterson said the lion died gnawing a fallen tree branch and clawing the ground, still trying to reach him.

The construction crew, learning of the deaths of the two lions, returned and finished the railroad bridge in February 1899. The exact number of workers killed by the Tsavo man-eaters is lost to history, but Patterson believed there could have been as many as 135 victims. Other, more moderate estimates range from 28 to 31 deaths. Regardless of the actual number of lives lost, Patterson ended the nine months of nightly terror at great risk to himself.

Over the years, hunters and wildlife biologists alike have speculated as to why the pair of Tsavo lions turned to preying on humans, and several possibilities have been cited. The most likely is that an outbreak of rinderpest disease (cattle plague) in Africa during the 1890s had devastated the lions’ usual prey, zebras and gazelles, forcing the cats to find alternative food sources.

After completing the railroad bridge project, Colonel Patterson became chief game warden in Kenya and later served with the British Army during World War I. He also wrote four books and lectured widely about his African adventures, the tale of the Tsavo lions being one of his most popular stories, garnering rapt, wide-eyed audiences. After giving such a speech at The Field Museum in 1924, he arranged for the sale of the two Tsavo lion skins and skulls to the museum for $5,000, quite a sum of money in those days.

Unfortunately, the skins arrived in poor condition, having been used as trophy rugs for a quarter of a century. In addition, the hides had bullet holes and thorn scratches. But museum master taxidermist Julius Friesser worked his magic on the hides, creating the life-like lion mounts that are still on display yet today.

Lastly, why were the man-eating lions of Tsavo mane-less? It turns out that not all male African lions grow manes. In a region as hot and dry as East Africa, heavy manes retain too much heat, so the big cats simply don’t grow them.

If you’d like to see an exciting, historically accurate Hollywood rendition of the man-eaters of Tsavo, pick up a DVD copy of the 1996 film titled The Ghost and the Darkness, starring Val Kilmer as Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson. Just don’t watch the movie right before bedtime, especially if you’re planning to go tent camping anytime soon.

Image by Superx308 Jeffrey Jung email: superx308 at gmail.com