--by Major Henry T. Stanton for the Kentucky Centennial held at Maysville, Kentucky, 1875

Along America’s frontier in the late 1700s, a woodsman had no more prized possession than his flintlock long rifle: a source of pride, provision and protection. And during that long-ago era, there was no more famous frontiersman roaming the Ohio River Valley than Simon Kenton (1755-1836), rivaling even the likes of Daniel Boone. In fact, author Frederick Palmer in his 1929 book Clark of the Ohio wrote, “Only a few white men were ever as good as the Indians at the Indian game. Boone and Kenton were…”

Born in Prince William County, Virginia, the black sheep of a large family, Simon Kenton ran away from home at age 15, ending up in Warm Springs in 1771 at a mill owned and operated by Jacob Butler. Hungry and in need of a place to stay, Simon lied to Butler, telling him that his last name was also Butler, not Kenton, hoping that the mill operator would think they might be distantly related and take him in. The ruse worked, and Simon spent the next several months eating at Butler’s table and working at his mill.

Young Simon grew to like the old man, thinking of him as a father figure. Likewise, Butler grew fond of Simon and tried talking him out of pursuing his dream of seeing the frontier. But eventually Butler realized it was no use; the young man was determined to head west. So he did the one thing he thought might help keep him safe—he gave Simon his favorite rifle.

In his classic book, The Frontiersmen, author Allan Eckert writes:

“The forty-inch octagonal barrel nestled in a forepiece of beautifully grained curly maple, and the stock, of the same wood, was decorated with an eight-point star and crescent moon in brass. The butt plate, trigger guard and patch box were also of brass, and the workmanship of the lock assembly was of the finest.”

Likely somewhere around .40 caliber, the rifle had been made by Henry Leman of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, especially for “those who deal with Indians in one way or another.” Butler also included a large shot pouch and brass powder flask. Simon Kenton was so awe-struck by such generous gifts that, with Butler’s approval, he quickly named his new rifle Jacob.

Less than a year later, Kenton was indeed living on the Ohio River frontier, making a living hunting and trapping, just as he’d hoped. And with him were two unlikely companions. One was George Strader, a lanky young man about Simon’s age; the other was John Yeager, an older man, somewhere north of sixty.

Much experienced in the ways of the wilderness, particularly tracking, Yeager had been captured at age four by Mingos and raised by members of that tribe. His main claim to fame seemed to be that he had been scalped by Shawnee Indians—enemies of the Mingos—and lived to tell the story. When Yeager removed his hat, it was easy to see he was not lying.

The trio was camped along the Great Kanawha River, a large tributary entering the Ohio along its south shore. Kenton trapped upstream, Strader downstream, while Yeager mostly stayed in camp doing the skinning, fleshing and stretching of the hides the other two men constantly brought in. It was an amicable arrangement, and all went well until late winter of their second year together.

It had been a raw, rainy early-March day, with both Kenton and Strader returning to camp near dark soaked to the skin and cold to the bone, their teeth chattering. They set their rifles in the back of the camp’s lean-to, well out of the weather, then stripped off their wet clothes and hung them to dry around the fire on sticks they jammed into the muddy ground. Nearly naked now, each of the two men wrapped himself in a dry blanket and hunkered down in front of the fire while Yeager heaped extra wood upon the coals.

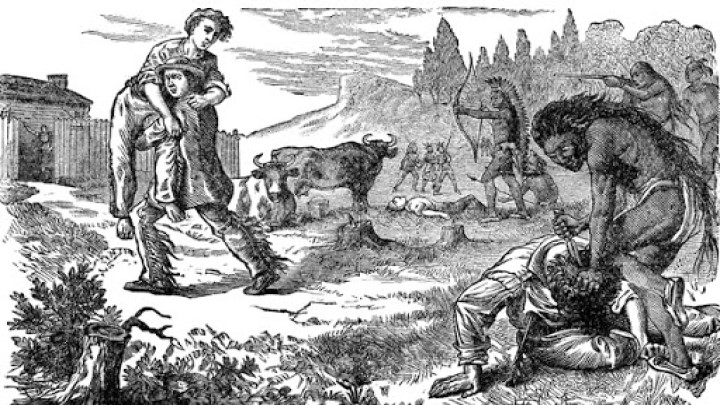

Simon was just starting to feel his body warming again when he glanced out into the growing darkness of the surrounding woods and couldn’t believe what he saw. Were his eyes deceiving him in his cold and hungry state? It took only seconds for his mind to confirm the danger. Half a dozen Indian warriors stood in a semicircle not 10 yards away, two of the braves with their rifles already shouldered and pointed at the three white trappers, ready to fire.

Instinctively, Simon screamed a warning to his two friends—“Meet at the bear trap!”—only a split second before the rifles roared. Kenton then threw off his blanket and plunged into the darkness to the right side of the lean-to, with Strader doing the same on the left. Unfortunately, it was too late for Yeager. A heavy round lead ball had already punched a thumb-sized hole through his chest, and the last thing Kenton remembered seeing was Yeager slumping to the ground beside the fire as one of the braves ran toward him with a raised tomahawk to finish the job.

Simon Kenton never ran so long, hard and fast in all his life. Tree branches and brush clawed at his head and naked body, as sticks and sharp rocks gouged his bare feet. He ran a mile or more before stopping to listen between ragged breaths, to see if he was being followed. Eventually confident he was not, he then headed in the direction of the lone bear trap, arriving about dawn. Strader was already there awaiting him, and the two young men were so glad to see each other alive that they wept as they hugged. But as relieved as they were it would be six more long, cold, hungry days before they staggered out of the woods and found help.

And adding to Kenton’s pain during that time was the knowledge that his beautiful rifle, Jacob, was now gone. He had had no time to make a grab for the gun before racing from the lean-to. He was heartbroken at having lost his prized flintlock, yet he was also very, very glad just to be alive…and he made up his mind to never again lean a rifle beyond easy reach while in the wilderness.

Over the next three decades, Simon Kenton would become a legend in the Ohio country as a frontiersman, scout and military advisor. Out of necessity, other rifles replaced Jacob, but none were as well-made, as handsome or seemingly as accurate. Nevertheless, many Indians fell as a result of Kenton’s prowess as a woodsman and wilderness fighter. Those encounters had been fair fights, with Kenton just as likely killed as the warriors, but somehow he had survived every battle. In retrospect, at age 53, he believed God had somehow providentially preserved him for some reason.