If you've spent most of your life at or near sea level, chances are you only have a vague idea of what a sudden and steep increase in altitude might do to your body. It's called altitude sickness or Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). Most of us have at least heard of altitude sickness, and know that it's related to the lower levels of atmospheric oxygen available at high altitudes. However, there are some pretty interesting (and sometimes counterintuitive) facts about it that you should know before you head for the hills.

1. Anyone can get it, and there's no way to tell ahead of time who it will be.

You'd think that young or highly physically fit people would be less likely to develop altitude sickness, but as it turns out, that's not the case. In fact, people older than 50 seem to be at a slight advantage when it comes to resisting the effects of altitude...although nobody really knows why. Even Olympic-level athletes can succumb to altitude sickness. Although previous experiences with altitude sickness (or its more dangerous variants, HAPE and HACE—more on that later) can indicate you're more likely to develop it again, those who have handled altitude changes easily in the past can still develop altitude sickness on subsequent trips.

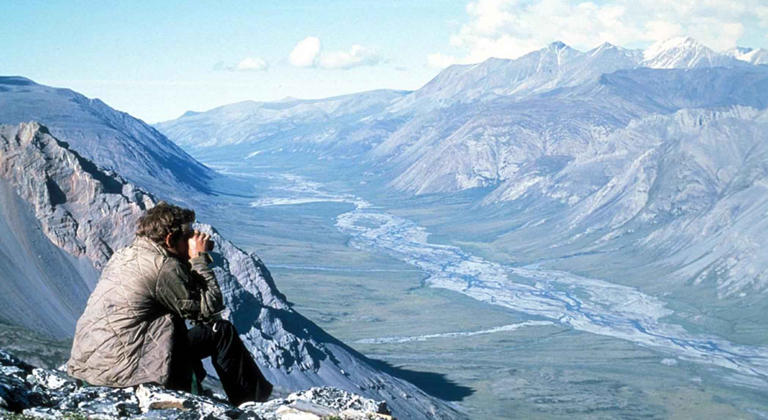

2. You don't necessarily have to be on a mountain to get it.

Although most people handle the level of oxygen available at about 8,000 feet above sea level just fine (in fact, that's the pressure level of the air you get inside an airplane), some people can begin to experience symptoms as low as 5,000 feet above sea level...which is just about a mile up. Denver, Santa Fe, Albuquerque and Colorado Springs are all major cities past the one-mile mark.

3. For most people, it feels like an alcohol hangover.

Altitude sickness in its mild form is remarkably akin to what most people report from an alcohol hangover: nausea, vomiting, persistent headache, lethargy, dizziness and unrestorative, troubled sleep. Although it can start within a couple of hours of your arrival at the high altitude, some people don't notice symptoms until after they've slept a night there. Counterintuitively, vigorous exercise will make it worse, not better. If you're experiencing the mild form of altitude sickness, your best bet (short of getting to a lower altitude) is to rest, get plenty of fluids and not push yourself too hard for a couple of days. Most people acclimatize within 24 to 72 hours. This is why, if you've booked yourself a once-in-a-lifetime Dall sheep hunt or an expensive ski vacation, you're better off getting to your destination a few days early to give your body time to get used to the high terrain.

4. When a person starts looking more like they're drunk than hung over, they're in trouble. Bad trouble.

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) is an acute form of altitude sickness that strikes about 1 percent of people who ascend past 3,000 meters (or 9,842 feet). Nobody's really sure what causes AMS to turn into HACE, but one thing is certain: It's extremely dangerous, and can be fatal within 24 hours of symptom onset. The symptoms themselves are very strange. A person suffering from HACE will behave almost as if they were drunk: confusion, extreme drowsiness, erratic behavior and loss of control of muscle movements are all hallmarks of the condition. Click here to learn what the CDC recommends to do for a person who may have HACE.

5. HACE is scary; HAPE might be even scarier.

HAPE is the acronym for another scary complication of altitude sickness: High Altitude Pulmonary Edema. It's a dangerous—and progressive—build-up of fluid in the lungs, and it can take a turn for the fatal in a matter of hours. Although HAPE is, like HACE, relatively rare, what makes it pernicious is that at first the sufferer will seem to be more or less fine. Symptoms don't usually develop until two or three days at 8,000 feet or above, and starts with the same "breathless" feeling experienced with mild altitude sickness. However, the sufferer will begin showing breathlessness even when they're at rest. They may have a rapid heart rate, high body temperature, and a pernicious cough with a "frothy" output, so it's also easy to confuse HAPE with a more benign chest infection. Click here to learn what the CDC recommends to do for a person who may have HAPE.

Have you ever had altitude sickness? Tell us your story!