A “Short” History

In recent years, we’ve seen a renaissance of short, efficient cartridges. It started with the 6.5 and 6 Creedmoor cartridges, but that quickly fell off with the idea of pushing those same small, aerodynamic bullets at hyper speed with cartridges like the 26 Nosler and the 6.5-300 Weatherby cartridge. Now, about a decade later, the short cartridges are coming back, but still pushing magnum-level velocities (in this case, we’ll use the term “magnum” to define cartridges that push heavy-for-caliber bullets faster than 3,000 feet per second--fps), in cartridges like the 6.5 PRC from Hornady and Winchester/Browning’s 6.8 Western.

But historical memory is "short," too, especially when it comes to cartridges. In the early 2000s we had a short-mag race between the original Remington with its Short Action Ultra Magnum (SAUM) cartridges, Ruger’s Ruger Compact Magnum (RCM) cartridges and Winchester’s Winchester Short Magnum (WSM cartridges). (And back then, the 6.5 Creedmoor wasn't even a thing!)

That mini arms race (pun definitely intended) wouldn’t last long, and Winchester won out. For the purposes of this article, the reasons aren’t important, but what is important is the line of cartridges we saw introduced, as some of them are still around today--and are still viable, even when compared to the modern offerings. One in particular is undeniably a standout. What cartridge might that be? The .300 WSM, aka the Winchester Short Magnum.

Back when it was launched, the .300 WSM was the best of the bunch of short magnums Winchester produced, which is why it’s essentially the lone survivor of the group (the .270 WSM still exists, but it’s in essence the 6.8 Western with a slower twist, so it can’t shoot long, heavy bullets as well as the 6.8 Western can). Winchester and Browning still make the .300 WSM in new rifles, but I’m sure each company does so in limited runs. Otherwise, custom rifle makers will probably make them for you if you want one. But the question is, should you want one? My answer: Most definitely.

Why WSMs?

When Winchester brought out the WSM line, there were a few reasons for it (these principles still hold true on the modern short magnum cartridges today, too). One, they made for lighter rifles simply based on materials. A longer or wider cartridge, like the .300 Win. Mag. for instance, needs a longer, beefier action. A short magnum, because of its inherent design, doesn’t need near as long of an action to cycle it. Because it’s a shorter action, it will also be more rigid.

Lastly, since the cartridge is shorter, its internal case capacity is smaller. That changes the pressure curve since there’s less volume inside the case when the powder charge goes, meaning that a bullet of equal weight can be propelled to a similar velocity by the smaller powder charge because the pressure pushing on the base of the bullet remains the same. Combining the material weight aspect and the smaller powder charge means more weight could be saved due to the WSMs not needing barrels as long as true magnums do. You see, the pressure curve falls off faster due to the smaller charge. They can reach magnum velocities without super-long 26" barrels before they get complete powder burn in the cartridge.

The Short of It

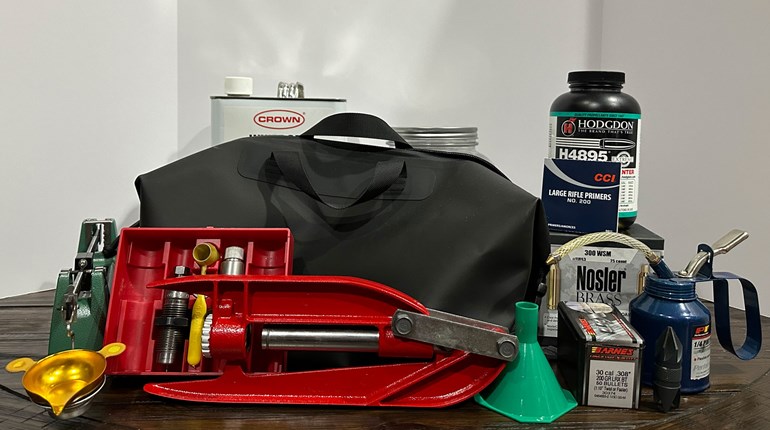

Aside from the overall efficiency of the cartridge--which is great if you reload your own ammo--why would you want a .300 Winchester Short Magnum? I’m again going back to the feats the cartridge pulls off if you reload for it when looking at cartridge application. I’ve had a Kimber Montana in .300 WSM for nearly two decades, and I’ve gotten some magic numbers out of this gun when it comes to ballistics. My home-brew load uses 62 grains of H4350 pushing a 200-grain Barnes LRX bullet to roughly 3,000 FPS.

That’s impressive in and of itself from such a small powder charge. But at the muzzle, I’m at nearly two tons of energy (3,864 ft.-lbs.), and out to 600 yards, I’ve still got nearly a ton of energy (1,981 ft.-lbs.). For reference, where I grew up hunting, state regulations required that big-game cartridges must “have an impact energy (at 100 yards) of 1,000 ft.-pounds as rated by manufacturer.” That means at 600 yards, I still have nearly double the muzzle energy required to hunt big game in that state. If it’s sufficient for a state government’s ethics, it’s good enough for my purposes.

Energy is great on impact, but if you can’t hit what you’re aiming at, it doesn’t matter; I’m covered there, too, as this load regularly prints 3-shot groups under an inch at my zero distance of 250 yards. This zero distance also allows me to never have to worry about printing any higher than 3" above my line of sight while ensuring my bullet drops about 4.5 feet at 600 yards, which is incredible, and about as far as I’d ever shoot that rifle, especially at a game animal.

Outside of hunting, I’ll admit, the cartridge might not appear as impressive as many of the new cartridges, like the PRC line cartridges from Hornady. But even then, that could change if you decide to change bullets to more of a match-style bullet with a higher B.C. value. And the efficiency of the cartridge is worth something (you’ll certainly save powder using the WSM variants over the 7mm or .300 PRC cartridges). Worst that happens is you run some numbers on a ballistics calculator, and you find out it’s not quite what you’re looking for. But what it lacks in flashy newness, it makes up for in the ability to keep up with the newest magnums.