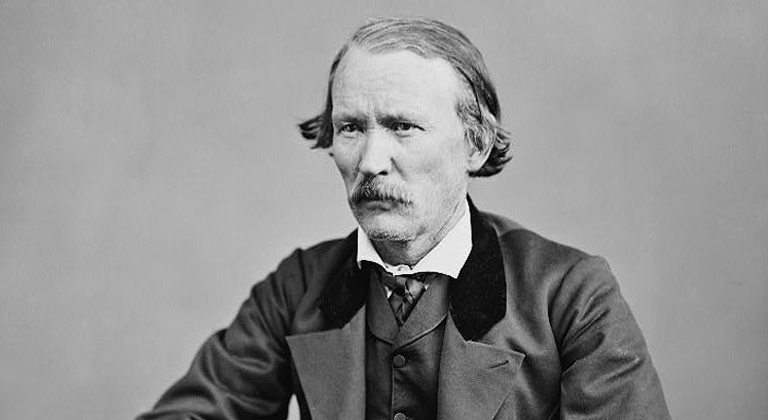

He stood just 5 feet, 4 inches tall and weighed but 140 pounds, yet Christopher “Kit” Carson was a giant of the American West, a legend in his own lifetime (1809-1868). Trapper, scout, explorer, Indian fighter, Civil War commander and more, he led a life salted with enough adventure and close calls that he should have died a dozen times.

Believing in signs and omens, Carson was a man of odd habits and peculiarities. For instance, when hunting he never took a second shot at game if he missed with the first round, which was seldom, considering it somehow “bad medicine.” But when he did kill an animal, he was fastidious about how he cleaned and dressed the carcass.

On the trail Carson had other rituals, not oddities but rather hard-won precautions meant to keep him alive. When bedding down for the night he always slept with his horse’s saddle at his head, for protection. Under the saddle he placed two pistols, at half-cock, and also slept with a rifle by his side. In addition, he never exposed himself to the full light of a campfire, just in case some enemy might be creeping up, looking for an easy target.

Born in Kentucky, Carson’s family moved to Missouri when he was just a year or two old. At age 14 he was apprenticed to a saddle maker, but hated the tedious, indoor labor—young Kit much preferred being outdoors. The only advantage of the job, it seemed to him, was hearing stories from the frontiersmen who occasionally visited the saddle shop. They told of the “shining mountains” far to the west where beaver and other “plews” were being trapped, and Kit Carson made up his mind to see those mountains. And sooner rather than later.

One night, Carson slipped away from his apprenticeship, hired on with a wagon train headed west, and never looked back. His first stop was Santa Fe, followed by Taos, the center of the Southwest fur trade. He soon fell in with various trappers and for the next dozen years made his living as a mountain man, learning wilderness skills. It was at the Green River rendezvous of 1835 that he cheated death for the first time.

It all started over a woman. Singing Grass was a beautiful Arapaho maiden attending rendezvous with members of her family. Carson, now age 25, was immediately smitten and longed to take her for his wife. But other white men had the same idea, in particular Joseph Chouinard, a French-Canadian trapper who was a giant of a man. Chouinard, well known as a bully, got drunk one night and challenged Carson. Because of the two men’s size difference, it would be a classic David-and-Goliath battle.

Both men immediately grabbed guns, mounted horses, and charged at one another, stopping so close that their horse’s heads touched. Both men fired simultaneously, at point-blank range, the shots sounding as one. Luckily for Carson, Chouinard’s horse shied as the Frenchman jerked the trigger and the shot went off course. The bullet grazed the side of Carson’s face, leaving a mark below his left ear he would carry the rest of his life.

Carson’s bullet, however, flew more true, tearing the thumb off Chouinard’s right hand. Before Carson could shoot again the big Canadian was begging for his life. As a result, Kit Carson won the fair Singing Grass’ hand and the two were married about a year later.

Although Kit Carson was proficient in all wilderness skills, it was his tracking ability that set him apart. A tale that illustrates his special talent occurred in 1854, when Major James Carleton hired Carson to help him and his troops recover horses stolen by Apaches.

The trail was stone cold by the time Carson located it, but he followed the hoof prints diligently for several days, the U.S. soldiers in tow. Finally, at breakfast one morning, Carson informed the major that today they would find the Apaches. In fact, Carson predicted, it would be about two o’clock that afternoon.

The major doubted Carson and told him so, going so far as to suggest a challenge. If Carson’s prediction held true, Major Carleton would buy him the best beaver-felt hat that could be purchased from New York City. The two men agreed on the challenge and shook on it.

It was early that afternoon that they spotted the Apaches, camped in a meadow not far from the Santa Fe Trail. The major pulled out his pocket watch and checked the time: 2:07 p.m.

Of the incident, Major James Carleton would later write, “Kit Carson is justly celebrated as the best tracker among white men in the world.” And the major made good on his promise, too. When the beaver hat arrived months later from New York, gilt lettering on the inside band read: At 2 o’clock, Kit Carson, From Major Carleton.

Kit Carson was married three times during his life. His first wife, the previously mentioned Singing Grass, died shortly after giving birth to their second child. Carson then was briefly married to another Indian woman, but that union lasted only a few months and they separated. His third wife was Josefa Jaramillo, a Mexican woman with whom he had eight children; making a grand total of 10 Carson kids in all.

In his narrated biography, Carson never mentioned his first two wives, believing that it would not be acceptable in certain parts of white society. Another personal embarrassment that Carson tried to hide all his life was the fact that he was illiterate.

As Kit Carson’s fame steadily grew—not only in the West but all across the fledgling United States—more and more people wanted to meet this larger-than-life frontiersman. But when they did, they were often disappointed. For instance, when William Tecumseh Sherman, a young army lieutenant who would one day become a famed Civil War general, met Carson he stated, “I cannot express my surprise at beholding a small, stoop-shouldered man, with freckled face, soft blue eyes, and nothing to indicate extraordinary courage or daring. He spoke but little, and answered questions in monosyllables.”

Another writer, George Brewerton, who had made a cross-country trek with Carson, wrote in an article for Harper’s Monthly magazine, “His voice is as soft and gentle as a woman’s. The hero of a hundred desperate encounters, whose life has been mostly spent amid wilderness where the white man is almost unknown, is one of Dame Nature’s gentlemen.”

A 20th Century biographer, Harvey L. Carter, summed up Carson’s life saying, “In respect to his actual exploits and his actual character…Carson was not overrated. If history has to single out one person from among the Mountain Men to receive the admiration of later generations, Carson is the best choice. He had far more of the good qualities and fewer of the bad qualities than anyone else in that varied lot of individuals.”

After a lifetime of near misses with premature death, Kit Carson died in bed of an aortic aneurism in May of 1868, at age 58. If you’d like to read more about the extraordinary life of Kit Carson, the book Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West, by author Hampton Sides, is highly recommended.