I've learned a lot from every firearms instructor I've trained with, but each and every one has that one certain thing, that single hint or instruction, that I carry with me on every range trip. It might be hearing “One shot, two sight pictures...” in Louis Awerbuck's South African accent or remembering Ernest Langdon's admonition to stop pinning the trigger to the rear, but there's always that one thing that really sticks with me.

With Todd Jarrett, it was hearing him yelling “Grip the gun 20 percent tighter!” at the whole firing line. “Twenty percent tighter than what?” you might ask, and the answer was 20 percent tighter than however tight we were gripping it right then.

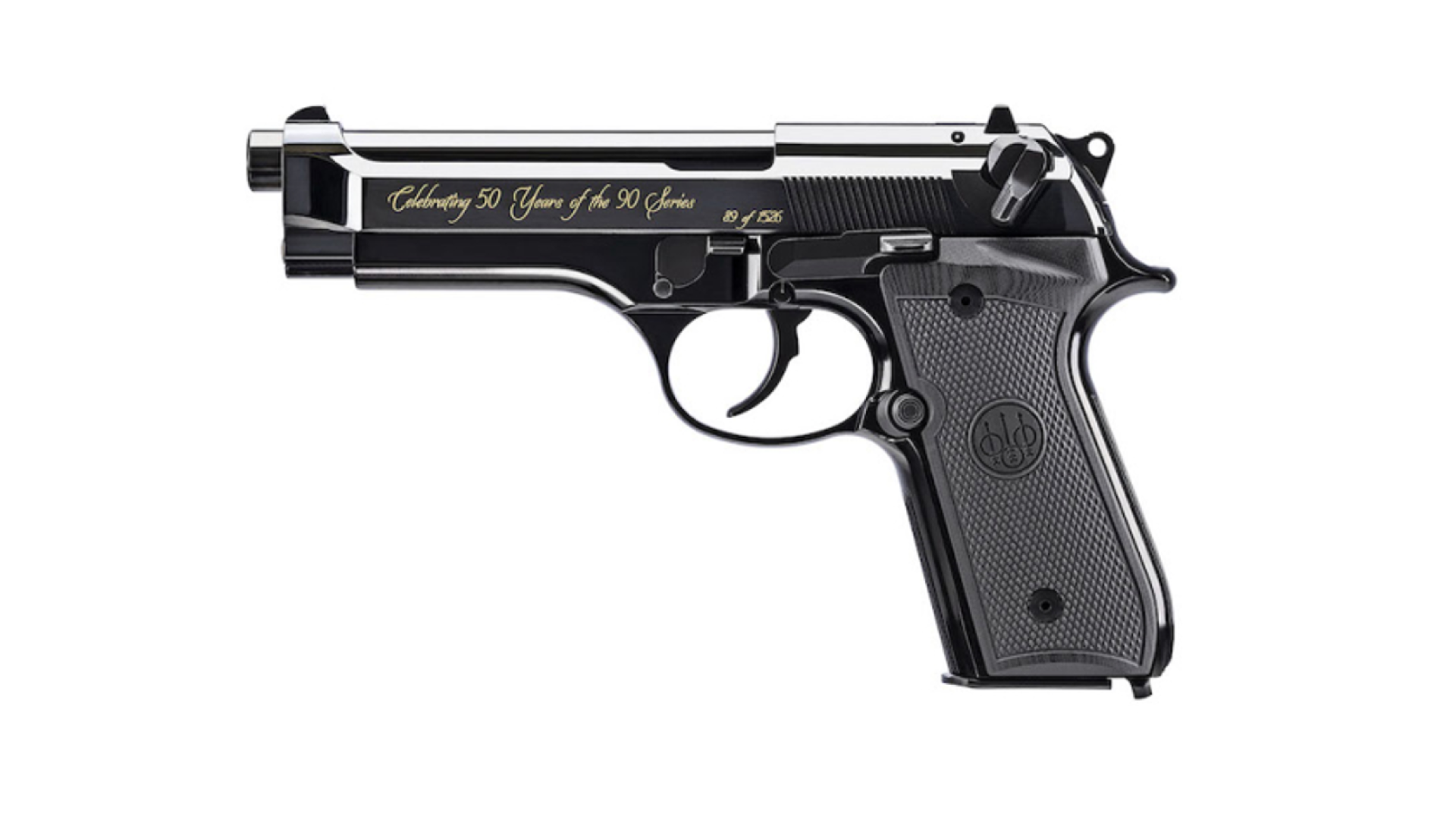

In slow-fire bullseye-type competition, the proper amount of grip on the gun is compared to everything from how you'd hold a live bird you didn't want to escape, to as tight as a firm-but-friendly handshake. In action pistol sports, however, where scores depend on getting one or more accurate follow-up shots as quickly as possible, a strong grip on the pistol is an important component of recoil control and getting those subsequent shots off in a hurry.

This has dividends in self-defense shooting as well, of course, and in more than one way. Obviously, there are still the benefits of recoil control, and this is important in a situation where multiple shots might be required to dissuade or stop an assailant.

The firm grip has a less-obvious benefit, and one that's actually grown more important with a couple of new trends in the firearms industry.

On the one hand, there has been a tremendous upsurge in slim, compact, lightweight pistols chambered for, not only the .380ACP, but also the 9x19mm cartridge. While the former is pretty potent for a pocket pistol round, the latter is a service pistol cartridge that has found a new niche in these tiny guns.

To make the 9mm work in these pistols with their diminutive slides and lightweight frames, all kinds of engineering tricks are done to slow the slide velocity down. These range from heavier, dual nested recoil springs to various internal mechanical leverage disadvantages the slide has to overcome to unlock from the barrel and travel rearward.

Simultaneously, a whole new genre of defensive ammunition has been developed, with marketing descriptors such as “Lite” or “Managed Recoil,” to indicate that the rounds won't be so jarring to fire from these tiny guns in duty chamberings.

What those easier-to-shoot rounds mean, however, is that there's less energy available to operate the slide of the gun when you fire it. On top of that, letting the gun move around in your hand under recoil acts as a sort of shock absorber; the energy expended in moving the whole gun around is not available to move just the slide relative to the frame.

What results from that is the dreaded “stovepipe” malfunction. The gun's slide will be jammed half-closed with the spent cartridge case sticking half out of the ejection port like a little chimney (as pictured above), and will have to be worked manually to get the empty out and the gun back in running shape.

What's the best way to prevent that in the first place? Just like Todd Jarrett was yelling at us, as it turns out: “Grip the gun 20 percent tighter!”