When Idaho Fish and Game veterinarian Mark Drew arrived at the ranger station, he was met with the pitiful sight of a badly injured bear cub. Boo Boo, as the four-month-old cub was named by his rescuers, was the victim of a forest fire that had destroyed his home and left him an orphan with four badly burned paws. He was unable to walk and hadn't eaten in several days.

The young bear had been discovered clinging to the branch of a fir tree and brought to the ranger's facility. But could he be saved?

The doctor went to work immediately, sedating the cub, checking for damage, administering medicine and bandaging the burned paws. It would be a long recovery, he thought to himself.

Over the next several days, Drew would care for Boo Boo, feeding him and bandaging and re-bandaging his wounds before transferring him to another facility. The cub would continue to be kept in isolation, his bandages changed often to make sure his wounds remained clean and free of infection.

In mid-September, just three weeks after the fire, Boo Boo was transferred yet again, this time to the Snowdon Wildlife Sanctuary near McCall, Idaho, for the final and lengthier phase of his recovery. “We'll hibernate him over the winter and release him in the spring," says Drew. “The saving grace is that his paws have healed, and he can function as a bear."

*****

Mark Drew knew he wanted to be a veterinarian in high school, but he was in college before he settled on becoming a wildlife veterinarian-a field that did not yet exist! At the time, “there were three or four individuals who functioned as wildlife veterinarians," says Drew, “but that was about it."

Still, Drew felt sure there was a way to combine the fields of veterinary science and wildlife management. He just had to find it.

Education

And finding a way meant education. Lots of it. Today, the route to becoming a wildlife veterinarian is a fairly defined path-a bachelor's degree that includes courses in wildlife management and veterinary studies, particularly the biological sciences, followed by a doctorate in veterinary medicine from a school with a wildlife medicine program.

But when Drew set out to become a wildlife veterinarian, there were no guidelines.And so it was that a bachelor's degree in wildlife management and biology was followed by a master's degree. Then came veterinary school. After a stint at a veterinary clinic, where the doctor treated small animals such as dogs and cats as well as horses and cattle, he tackled a residency in wildlife medicine through the University of California at Davis.

Finally, the young doctor was ready to pursue his passion. His early jobs were for wildlife management agencies and universities. Ten years later, Drew would land the “cool job" of wildlife veterinarian at Idaho Fish and Game.

A Day in the Life

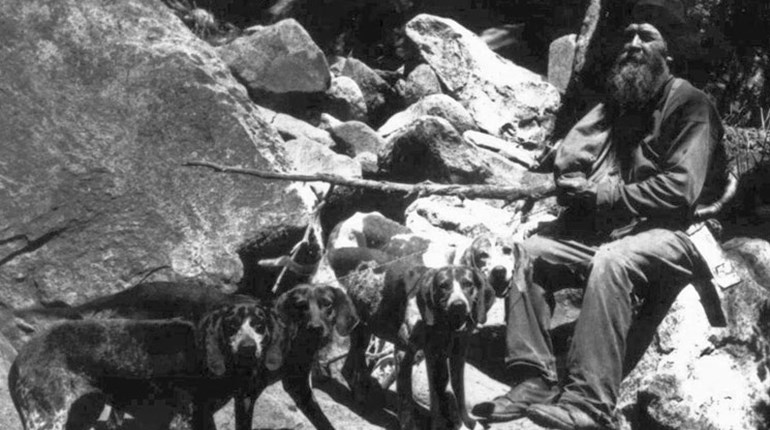

Drew's daily tasks actually change from season to season. From November to March, he spends a lot of time out in the field working on things like animal capture-everything from deer to wolves, sheep and waterfowl-and collecting samples like blood.

“Field capture," says Drew, “is the high-drama, high-excitement part of this job." For instance, as part of Idaho Fish and Game's efforts to ensure the survival of bighorn sheep, the animals may be fitted with a radio collars, marked, measured, examined for health issues and even captured and relocated.

“We jet boat up the river 50 or 60 miles to a fish and game cabin," says Drew.

Then they make their way through rapids to get close to the beach, or climb the steep slopes in pursuit of the animals. Now bighorn sheep, like all wild animals, want nothing to do with humans. So they need to be darted with a sedative before they can be handled. The trick is getting close enough to do the deed. “We have to get within 20 or 30 yards to be able to dart them," explains Drew, who clearly revels in the excitement of the chase.

“It's pretty cool. It makes you say to yourself, “People pay me to do this?" says Drew, laughing.

In contrast, a typical fall activity involves getting ready to keep a close watch on disease in the animal populations and deciding how to go about that. And, of course, there are certain tasks that take place year-round. “If you get a call about a moose in town, you have to deal with it," says Drew.

Or a call about an injured animal, like Boo Boo. Then there are the necropsies, which are animal biopsies, another area that seems to spark Drews's interest. “Necropsies are about detective things," say Drew with enthusiasm. “What happened? How did it die? What did it die of?"

“When you get those answers," continues Drew, “the next step is to figure out what it means for the population from which the animal came. For instance, if it's afflicted with a bacterial disease and has pneumonia, is a pneumonia outbreak going on and what needs to be done about it?"

Other necropsies might involve investigating an illegal activity. “If there's a bullet hole in the hide of a dead moose, you have to figure out bullet trajectories and how it [the killing] happened," Drew explains. “It's about solving a mystery."

Highs and Lows

Of course, being a wildlife veterinarian has its highs and lows. For Drew, the high point is working up close and personal with animals. He enjoys making sure they are healthy and being taken care of properly. He likes knowing that he has collected information about them and worked with them, and that when they return to the wild, they'll do well. “It's really satisfying," says Drew.

His least favorite part of the job, which Drew claims isn't really all that bad, is the paperwork. “There's a lot of it," he explains. “Reports. Research summaries. I enjoy writing, but compared to jumping on an elk, sitting at a desk is the lower end of the spectrum."

Still, says Drew, “It's part of the job. It's necessary."

Is It For You?

Wildlife veterinarians work in zoos, in wildlife rehabilitation facilities and in the wild. So the first thing you need to do is think about which would interest you most. If you want to be mostly hands-on with medicine and surgery, you'll probably want to look into zoo or rehabilitation work. Or you might like the idea of dealing with the big picture, as Drew does-studying entire populations of animals to “see what's happening disease-wise," often working in the outdoors and occasionally doing surgical or medical work on an individual animal. If so, then becoming a wildlife veterinarian who works in the wild may be the “cool job" in your future.

Five Tips on Becoming a Wildlife Veterinarian

- Try to get as much experience with veterinarians (including standard dog and cat veterinarians) and wildlife personnel as you can. “You need to get a handle on both fields," says Drew.

- Talk to people in the veterinary and wildlife management fields-local vets, wildlife veterinarians, and wildlife managers and rehabilitators, including those at state and federal agencies. Ask what they do and how they got there. Get their recommendations. And when you're old enough, volunteer with people in these professions.

- Plan on studying both the veterinarian curriculum and wildlife management for your undergraduate college degree.

- The other thing to bear in mind is that there are not that many non-zoo wildlife veterinarian jobs out there. Twenty-five years ago when Drew was getting started, there were maybe three or four people serving as wildlife veterinarians. “Now," says Drew, “there are close to 25 or 30 in state or federal wildlife programs. That leaves another 20 states that still need to get into the ballgame."

- The field is growing, but it's growing slowly. By contrast, there are plenty of jobs in the zoo world. So a lot of would-be wildlife veterinarians start in zoos and transition to state and federal fish and game programs, and vice versa.