** When you buy products through the links on our site, we may earn a commission that supports NRA's mission to protect, preserve and defend the Second Amendment. **

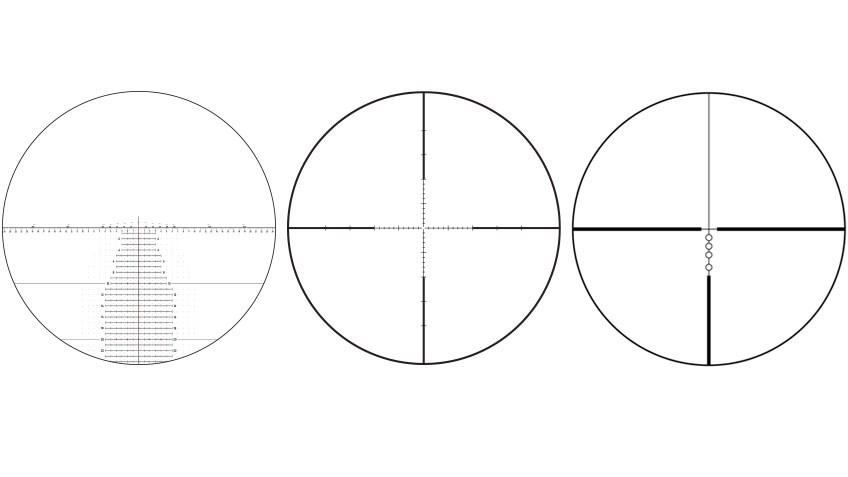

The riflescope's reticle is the visible reference used as an aiming point to align the gun with the target. There are many reticle patterns ranging from simple to complex. The most popular remains the general-purpose crosshair. However, even the simple crosshair offers choices, such as tapered, ultra thin, duplex, mil-dot, ballistic compensating, range-finding, center dot, center ring and post, just to name a few. Eac configuration is intended for a specific type of use and there are multiple versions of all. For example, tapered crosshairs are a popular choice for varmint hunting and duplex crosshairs are a common choice for big-game hunting. There seems no limit to new reticle designs being offered, and most makers offer at least six or more types. Your best bet is to try out several at a local gun store, then consult with experienced shooters or hunters before making a final selection.

Reticles may be illuminated electronically, with tritium or with fiber optics to enhance their contrast against dark backgrounds, especially at dusk or dawn or during heavy overcast conditions. Illumination remains an expensive option that may not work well in very cold conditions and has limited usefulness. Still, it has proven a popular addition to many scopes.

The reticle itself may be located inside the scope at the first, or front, focal plane or the second, or rear focal plane. The location is an issue only in variable-power scopes. Reticles located in the first focal plane in a variable-power scope will increase or decrease in size as the magnification is changed while those located in the second focal plane do not change size when the power is adjusted. For this reason, the latter location has become the most popular.

One situation in which a front-focal-plane reticle is clearly advantageous is in scopes with a mil-dot ranging system. This type of reticle employs dots spaced one milliradian apart on the crosshair. (A milliradian is the angle subtended by 3 feet at 1,000 yards.) An object of known size is bracketed between the dots, and a table is used to determine the range based on the number of dots the object measures. With a rear-focal-plane reticle variable, the mil-dot system is only accurate at one power setting. A front-focal-plane location maintains the same relationship to the target throughout the range of magnification, thus enabling mil-dots to be used accurately at any power.

A second benefit of placement in front of the variable-magnification lens system is that the reticle remains unaffected by tolerances or misalignment of the erector tube during power changes. With a rear-focal-plane location, these tolerances may shift point of impact as the power level changes.

In the past, many scope reticles were not constantly centered, meaning they moved off to the side when windage or elevation adjustments were made. Many shooters found this annoying. Today, nearly all riflescopes have constantly centered reticles that do not change position when adjustments are made.

Crosshairs or other reticle patterns are created by laser edging on optical glass or by ultra-thin platinum wires. Some early scope reticles used strands of hair, hence the name "crosshairs." Others used spider silk...interestingly enough, the silk of the black widow spider, which has a better tensile strength than other types of spider silk.

Reticles may be illuminated electronically, with tritium or with fiber optics to enhance their contrast against dark backgrounds, especially at dusk or dawn or during heavy overcast conditions. Illumination remains an expensive option that may not work well in very cold conditions and has limited usefulness. Still, it has proven a popular addition to many scopes.

The reticle itself may be located inside the scope at the first, or front, focal plane or the second, or rear focal plane. The location is an issue only in variable-power scopes. Reticles located in the first focal plane in a variable-power scope will increase or decrease in size as the magnification is changed while those located in the second focal plane do not change size when the power is adjusted. For this reason, the latter location has become the most popular.

One situation in which a front-focal-plane reticle is clearly advantageous is in scopes with a mil-dot ranging system. This type of reticle employs dots spaced one milliradian apart on the crosshair. (A milliradian is the angle subtended by 3 feet at 1,000 yards.) An object of known size is bracketed between the dots, and a table is used to determine the range based on the number of dots the object measures. With a rear-focal-plane reticle variable, the mil-dot system is only accurate at one power setting. A front-focal-plane location maintains the same relationship to the target throughout the range of magnification, thus enabling mil-dots to be used accurately at any power.

A second benefit of placement in front of the variable-magnification lens system is that the reticle remains unaffected by tolerances or misalignment of the erector tube during power changes. With a rear-focal-plane location, these tolerances may shift point of impact as the power level changes.

In the past, many scope reticles were not constantly centered, meaning they moved off to the side when windage or elevation adjustments were made. Many shooters found this annoying. Today, nearly all riflescopes have constantly centered reticles that do not change position when adjustments are made.

Crosshairs or other reticle patterns are created by laser edging on optical glass or by ultra-thin platinum wires. Some early scope reticles used strands of hair, hence the name "crosshairs." Others used spider silk...interestingly enough, the silk of the black widow spider, which has a better tensile strength than other types of spider silk.