Our earliest colonial governments began with charters written for individuals and settlement companies. As colonists sought religious freedom, better land or escape from British rule, charters were authorized by the King as the legal means for the colonies to exist.

As the colonies became more independent, they established their own governments, even drafting state constitutions in some cases. During this same period in our history, complaints began to surface about the perception that traditional rights of English citizens were not being extended to the colonists. Similar unrest was vented in Jonathan Mayhew’s sermon where he coined the phrase "No taxation without representation." These and other objections to British oversight led to the American Revolution, during which the colonies formed the Continental Congress, declared independence on July 4, 1776 and fought the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783).

Eleven years after publishing the Declaration of Independence with the legendary words “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” representatives from the 13 states were invited to Philadelphia’s Independence Hall to revise the “Articles of Confederation.” These Articles still recognized states as independent governments. After the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781, colonial activists began to compare the viability of independent state governments to a federal government better suited to national affairs. By 1786, it was apparent that the Union would not last unless the Articles of Confederation were revised.

Absent Rhode Island, the Philadelphia meetings began on Friday, May 25, 1787, with 55 prominent citizens attending. The deliberations included alternatives for wartime security, transitioning to a central government and how the states would be represented in that central government. The more populated states preferred proportional representation, while smaller states argued for equal representation. Thanks to the remarkable wisdom for our forefathers, the matter of state representation was resolved by proportional representation in the lower house (House of Representatives) and equal representation in the upper house (Senate).

As the summer debates of 1787 wore on, emphasis gradually shifted from state rule to a central, federal government. However, with little mention of individual rights guarantees written into the draft, several delegates, including anti-federalist George Mason of Virginia, proposed that a committee be appointed to prepare a bill of rights. Mason concluded in his objection: This government will commence in a moderate aristocracy. It is at present impossible to foresee whether it will, in its operation, produce a monarchy or a corrupt oppressive aristocracy. It will most probably vibrate some years between the two, and then terminate in the one or the other.

One hundred and sixteen days after convening, 39 delegates signed the carefully crafted system of checks and balances that would become the United States Constitution. As provided for in Article VII, the document would not become binding until it was ratified by nine of the 13 states.

The following summer, New Hampshire became the requisite ninth state to ratify the document, thus establishing our new form of federal government. Today, our Constitution is the oldest written, operating constitution in the world.

Mason’s objection was delivered five days before the Constitution was signed. Perhaps due to the months already spent in argument and debate, and maybe to some degree because of the summer climate, worsened by the heavy wool coats and wigs of the day, the anti-federalist’s proposal was rejected.

Those who supported the Constitution were known as federalists. Delegates who feared that a centralized government would lead to a dictatorship were called anti-federalists. Recall that our fledgling country had just fought a war over matters such as “taxation without representation,” so there remained a healthy resistance to replacing one autocratic government with another. As a result of the impasse over the proposed amendments, several delegates refused to sign the final document.

Negotiating a common, legislative rule of law for 13 states, in four months (not years) and securing a majority vote was an extraordinary task in itself. Devising a system of checks and balances with separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches was brilliant. But in 1787, the completed document contained none of the civil liberties that distinguish our government today. Were it not for the inspired, flexible design of the newly drafted Constitution that allowed a minority group to voice a dissenting opinion, the cornerstone of individual rights on which our democracy is now based may never have been laid.

The early framers recognized the need for flexibility in constitutional law. Consequently, Article V of the Constitution outlines the method for change as a two-step procedure: Proposal of an amendment, followed by ratification. Using state models for individual rights and reaching as far back as the English Magna Carta for inspiration, Mason proposed a Bill containing 10 amendments to the Constitution what became known as the Bill of Rights. Through a lengthy process of House, Senate and State ratifications, the Bill was ultimately signed four years later on December 15, 1791. Over time, more than 5,000 amendments have been proposed in Congress, with far fewer actually ratified.

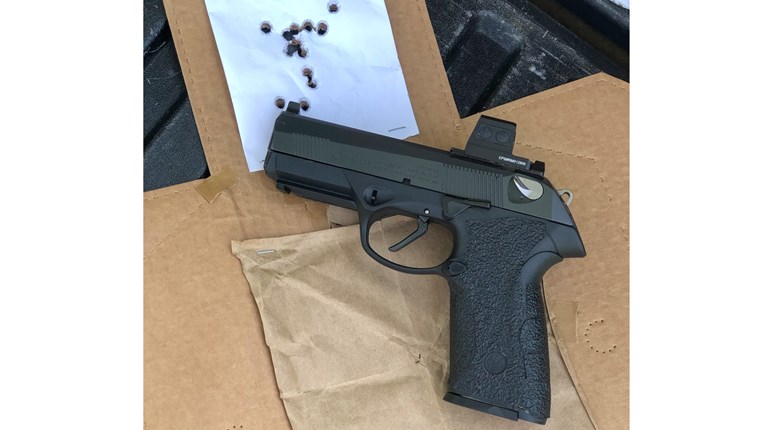

Established shortly after the American Civil War (1871) as a marksmanship and firearms safety organization that today includes a myriad of related education and support programs, the National Rifle Association’s mission was significantly expanded in the mid-1970s. With an increased concentration of resources devoted to preserving Second Amendment rights, NRA became a more active participant in the legislative and public policy arena in support of protecting and advancing the guarantees of our Constitution. As originally ratified by the founding fathers, the Second Amendment decrees that:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.This wasn’t a new concept, with origins dating back to Great Britain’s Bill of Rights written in 1689. The British version created a separation of powers, enhanced democratic elections, bolstered freedom of speech and argued that individuals had the natural right of self-defense.

The old style grammar used when drafting the Second Amendment has since led to multiple dissections and interpretations of the founders’ intent. Were the framers referring merely to the need for a standing militia, or is it clear that their focus was to preserve an individual right, as was the theme for all 10 amendments?

Over the years, the Supreme Court has rendered its own interpretations of the intent of the Second Amendment. In 1875 (United States v. Cruikshank), the Court ruled that "the right to bear arms is not granted [emphasis added] by the Constitution; neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The Second Amendment means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress, and has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the National Government."

Fast forward to 2008 (District of Columbia v. Heller), where the Court again ruled that the Second Amendment "…codified a pre-existing right" and that it "…protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home." Most recently in 2010, (McDonald v. Chicago), the Court ruled that the Second Amendment limits state and local governments to the same extent that it limits the federal government.

While it’s interesting to review the twists and turns of history and the awe-inspiring wisdom of the founding fathers, what lies ahead rests squarely on our shoulders. Readers will argue their own reasons why the fervent debate continues over the Second Amendment and, by extension, gun control. I believe that the implementation of Social Security (1935), the shift from an agricultural to urban life, and a dependence on others for food, shelter and safety, and maybe even the advent of 911 calls (1968), have contributed to an attitude, for many, that “someone else” is responsible for our welfare. The opposing side will argue that we are “our own 911.”

With the recent Republican wins in the White House and Congress, and the Supreme Court nominations to follow, one could mistakenly believe we have put this debate to bed for 40-50 years. Whether or not the argument can be reconciled through education, arbitration or compromise, that’s another article – for all of us to write.