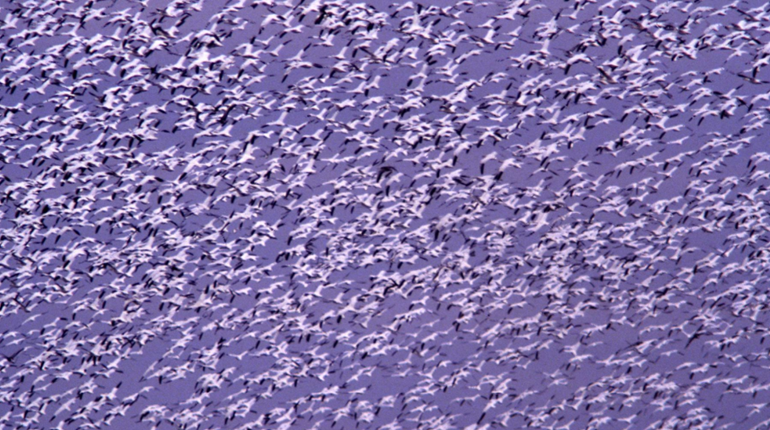

In all of North America, there is no more iconic waterfowling locale than Chesapeake Bay, where for centuries hardy, weathered watermen have hunted ducks and geese migrating by the tens of thousands. A huge region encompassing a 65,000-square-mile watershed, the area consists of not only the open waters of the bay but countless contiguous marshes, rivers and streams, most any one of which are perfect for spending a day in the blind.

Located halfway down the bay on Maryland’s Eastern Shore is the small town of St. Michaels, home of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. One of the 15 buildings on the museum grounds is dedicated entirely to duck and goose hunting, and is filled with original punt guns, shotguns, hand-carved decoys, classic wooden hunting boats and all manner of other waterfowling paraphernalia. Especially fascinating are the details of how the various pieces of equipment were once used. Here are four weird (and now illegal) old-school waterfowling techniques from the Chesapeake Bay.

1. Punt Guns

Outlawed many years ago, punt guns were used by commercial waterfowlers to kill as many ducks, geese and swans with one shot as possible. In essence, a punt gun was a giant muzzleloading shotgun—a small cannon, actually—measuring 10 to 12 feet long and weighing 100 pounds or more. The gun was so large and heavy it could not possibly be fired from the shoulder. Rather, a punt gun was mounted in a skiff, also known as a punt, hence the name punt gun.

These giant guns were used at night and mainly during the winter months when waterfowl rafted in large numbers well offshore. The hunter spotted his quarry at dusk, beginning his stalk after dark. Lying next to the gun, he would take a small paddle in each hand and slowly propel the wooden skiff within range, about 30 to 50 yards. Aiming was accomplished by sighting along the gun’s barrel. When the trigger was finally pulled the 2-inch bore roared, lighting up the inky blackness for a split second. In the aftermath, as many as 100 or more waterfowl were blasted from the water. One bayman referred to his punt gun as his “headache gun,” for he’d have to take a couple aspirin after each shot to reduce the jarring effects of the muzzle blast.

Although many species of waterfowl were shot and sold by Chesapeake Bay market hunters, it was the canvasback that was most prized because it fed mainly on wild celery which flavored the meat. A large diving duck, “cans” as the species is still referred to by modern-day hunters, were so delicious that they were offered as a high-priced delicacy in the finest restaurants in nearby Baltimore.

A variation of the punt gun was the battery gun, anywhere from three to 12 large-gauge shotgun barrels arranged in a fan configuration and attached to the front of a boat. When the first barrel was fired, the other barrels went off rapidly, one after the other, sending fearsome loads of shot downrange. Gunning lights were sometimes used at night, as well. Mounted in the front of a boat the bright light mesmerized waterfowl—similar to a deer caught in headlights—such that a hunter could float within shotgun range.

2. Sink-Box Hunting

During daylight hours, sink-box hunters ruled the bay. Upwards of 50 rigs worked the Susquehanna Flats area of the upper bay alone, used by both market hunters and sportsmen. Sometimes called a coffin box, the sink box was coffin-shaped, made of wood or metal, and just large enough for one hunter to lie in on his back. The sink box was anchored in open water where large wooden wings were attached. Heavy, steel waterfowl decoys with flat bottoms were placed on top of the wings to sink the top edge of the box to the surface of the water.

Traditional wooden decoys, as many as 300 to 500, were then placed around the sink box. Once everything was set, a hunter was virtually invisible to ducks and geese approaching low over the water. The closest thing modern-day waterfowlers have to experiencing sink-box shooting is hunting from a layout boat, which sits low to the water line but not below it. Sink-box hunting was eventually outlawed by the state of Maryland and the federal government in the same year, 1935.

3. Body-Booting

As a substitute for sink-box hunting, Chesapeake waterfowlers developed what was known as body-booting. Used in shallow water, a hunter put out a large spread of decoys, then, while wearing a pair of waterproof waders and hiding behind a goose silhouette decoy, simply stood motionless in the middle of the decoys and waited for waterfowl to fly within shotgun range. Standing in 3 to 4 feet of water, it was often difficult for a hunter to keep himself, his shotgun and ammunition dry, especially on windy days.

4. Live Decoys and Tolling Dogs

Decoys have always played a large part in waterfowl hunting because the “Judas birds” are so effective. Ducks and geese, being flocking birds, are naturally attracted to others of their kind. Chesapeake hunters made their decoy spreads even more enticing by adding live birds to their wooden blocks. Both ducks and geese were used. Live ducks, usually mallards, were tethered among the wooden decoys and would flap their wings, splash water, and call incessantly to wild ducks approaching overhead. Some geese were even trained to fly to wild flocks of geese and lure them back within range of the gunners.

A little-known decoying technique took advantage of the natural curiosity of some species of waterfowl. Hunters, hidden in a blind along the shore, would use a tolling dog. At times, ducks would be attracted to a decoy spread but land just out of effective shotgun range. If the ducks could not be enticed to swim closer by using a duck call, it was then a hunter began throwing a stick on shore parallel to the water’s edge and having his tolling dog retrieve it, time after time. While doing so, the hunter made sure to remain in the blind, well hidden from the ducks. If he was patient and persistent, and the dog ignored the approaching ducks as it was trained to do, the ducks often swam within easy shotgun range.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 was the beginning of the end for punt and battery guns, sink-box shooting, and the use of live decoys. The treaty also ended market hunting of waterfowl. The late 1800s and early 1900s are thought of today as the golden age of waterfowling on Chesapeake Bay. Yet, ultimately, it was unsustainable—the unregulated hunting methods of the time were just too devastating for waterfowl.

If you’d like to read more about those years, the book The Outlaw Gunner by Dr. Harry M. Walsh, a native of the Chesapeake Bay area, is highly recommended. If you’d like to read more about punt boat hunting in particular, click here.