Japanese soldiers thought it sounded like English being spoken underwater. American soldiers thought it sounded like Japanese. But to the U.S. Marine Corps Navajo code talkers themselves, their native language was a comforting, soothing sound, reminding them of their families and the homes they were fighting for thousands of miles away on the Indian reservations of America’s desert southwest.

The United States was ill prepared for World War II. Though war clouds had been gathering for years during the 1930s, America hoped to remain neutral in the growing worldwide conflict. All that changed on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Hawaii was not a U.S. state at the time, and would not become our 50th until 1959. But the island of Oahu contained a main naval base of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, making Pearl Harbor a prime target.

In retaliation for the bombing, the U.S. Congress declared war on Japan the next day, December 8, 1941. In response, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S. a few days later. Thus, the great conflagration of World War II was ignited, and the deadliest conflict in human history was underway. As a result, an estimated 70 to 85 million fatalities would occur worldwide, with more civilians killed than soldiers.

Early in the war, the Japanese military had the upper hand in the South Pacific, their navy dominating the sea and their army overrunning island after island. And they had little trouble cracking the supposedly secret communication codes of the U.S. military. Obviously, an absolutely unbreakable code was needed, but how to develop one?

Phillip Johnston, a civil engineer, is credited with the idea of a secret code based on the Navajo language of native Americans. Johnston, the son of missionary parents, had been raised on a reservation and knew the Navajo language to be complex, extremely nuanced, and very difficult to learn. The Navajo language, at that time, was also unwritten, so could not be learned from a book.

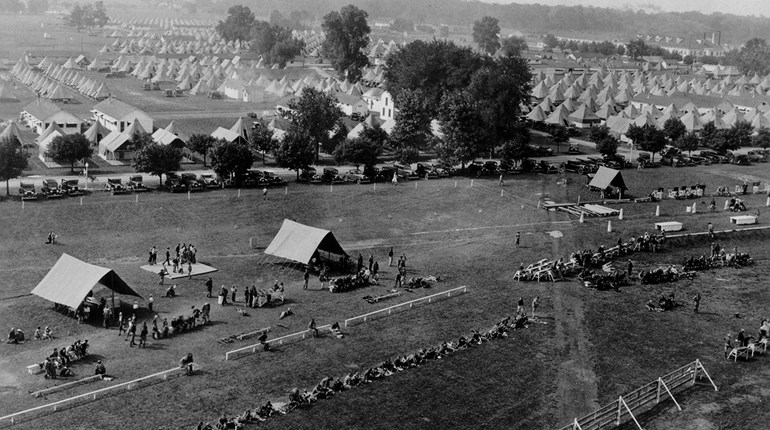

The Marine Corps brass was eventually convinced to take a chance on the scheme. Recruiting 29 Navajo young men for the top-secret assignment in May of 1942, the group was first put through the standard seven-week basic training course at San Diego, California—at which the 382nd Platoon excelled, particularly on the rifle range. Upon graduation, the group was then informed of their ultimate mission. Locked in a classroom by their commanding officer, they were told to come up with a radio communications code utilizing the Navajo language.

What ultimately resulted was a Navajo word for each letter of the English alphabet. The code words were carefully chosen so as to be clear when spoken over a radio, and each word was distinct from the other words chosen. An English word, usually an animal or plant, was selected to represent each letter of the English alphabet. For instance, the letter A became “ant.” Not the English word for ant, but the Navajo word, pronounced wol-la-chee. The letter B became “bear,” pronounced shush in Navajo; and so on through the alphabet. Thus, a double encryption became part of the code, making it even more difficult to crack.

The code was developed over a period of 13 weeks and contained some 700 Navajo words. Expert U.S. military codebreakers were then challenged to decipher the code, but after weeks of trying none was successful. The next test would come in the field.

Shipped to Guadalcanal, an island in the South Pacific, the code talkers reported to a Lieutenant Hunt, a signal officer who doubted the Navajo code system would work reliably, especially under the pressure and stress of enemy fire. As their first test, the officer gave the men a message he estimated would take four hours to encode, transmit, receive and decode using the current, so-called Shackle system.

Using their new system, the code talkers successfully sent and received the complicated message in just two and a half minutes—accurately, word for word, without a single mistake. Hunt was impressed, but as he and everyone else knew, the ultimate test would come during combat.

In his book, Code Talker, Chester Nez, one of the original 29 Navajos, recalled his first battlefield transmission on Guadalcanal. “A runner approached, handing me a message in English. I’ll never forget it: ‘Enemy machine-gun nest on your right flank. Destroy.’ Suddenly, just after my message was received, the Japanese guns exploded, destroyed by U.S. military.”

Code Talkers always worked in pairs. The portable radios they used were the size of a large shoebox and weighed about 30 pounds. To operate a radio, one code talker constantly turned a hand crank, generating electricity, while the other man transmitted and received messages. Both men wore headphones, connected to the radio by wires, so they could hear one another as well as the transmissions.

Japanese soldiers were adept at determining where U.S. radio signals originated, so it was important for code talkers to change their location immediately after a transmission. Wait too long and enemy mortar shells would begin raining down. Code talkers also changed their radio frequency every day to confuse the enemy.

Over time, the ranks of the code talkers grew to include some 400 Navajo Marines, 13 of whom were killed in action. Their unique, historic code ultimately proved so successful that it became one the U.S. military’s most closely guarded secrets, not declassified until 23 years after the conclusion of WWII. It remains the only unbroken code in the history of modern warfare, saving untold numbers of American lives and helping win the victory over Japan in the South Pacific.

The code talkers experienced all the unspeakable horrors of war, yet persevered, completed their mission, and in the process gained the respect of both enlisted men and officers. One fellow Marine, a non-native, said of them, “The Navajos were extremely dependable. They were the kind of guys you wanted in your foxhole, so I always tried to choose them when something had to be done.”

Major Howard Connor, a 5th Marine Division signal officer, had six Navajo code talkers working around the clock during the first two days of the battle for Iwo Jima. The six sent and received more than 800 messages, all without error. Connor later said, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”

Near the end of the war, the code talkers had become so indispensable that bodyguards were assigned to them, two per Navajo. Said Chester Nez, “I don’t know whether our bodyguards had orders to kill us rather than allow us to be captured. The Marine Corps has been asked if this was so, and they did not deny it. I believe that an American bullet would have been preferable to Japanese torture. At any rate, no code talker was ever executed by his bodyguard.”

The last surviving code talker of the original 29, Chester Nez died on June 4, 2014… Semper fi.