The Great Plains of North America, 1.1 million square miles that at one time in history was a vast sea of prairie grasses, was once ruled by numerous tribes of Plains Indians. Some of the best horsemen in the world, the epitome of that horse culture was the Comanche tribe whose skills on horseback were legendary, awing plainsmen and cavalry soldiers alike.

For instance, while riding a war pony bareback at full speed, a Comanche warrior could slide off onto the side of the horse—in essence, keeping the animal’s body between himself and an enemy—and return fire accurately with a bow and arrows by shooting from beneath the horse’s neck. Horses were valued in Comanche culture not only for warfare, but buffalo hunting, as well. They also served as symbols of status and wealth—the more horses the better. The average warrior kept a hundred or so on hand; a chief might have a 1,000 or more head grazing near his tipi.

But all that largesse came to an end in the late 1800s when professional buffalo hunters began arriving on the Great Plains. Between 1868 and 1881 alone, commercial hunters killed 31 million buffalo for their hides and tongues—the salted tongues were considered a delicacy in Eastern restaurants—leaving the carcasses to rot.

Surprisingly, government officials did not condemn such slaughter; rather, they actually condoned it. U.S. Army General Phil Sheridan wrote:

“These men [buffalo hunters] have done in the last two years … more to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last thirty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary … For the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle and the festive cowboy.”

The Indians were rightfully enraged by what they were witnessing, realizing that if the wholesale killing continued it would soon end their nomadic way of life, as they depended upon the buffalo for their very existence. They decided a series of raids was in order, and that their first target would be Adobe Walls, a small frontier trading post in the Texas Panhandle frequented by buffalo hunters.

A previous frontier fight had happened near that location a decade earlier, in 1864. Known as the First Battle of Adobe Walls, the famous frontiersmen Kit Carson had led soldiers against a combined force of Comanches and Kiowas. But Carson and his scouts badly miscalculated the numerical strength of their enemies, barely escaping a Custer-like massacre.

Chosen to lead the Indian attack this time was Quanah Parker, a young yet proven warrior with an unusual family background. He was the son of a prominent Comanche war chief (Peta Nocona) and a white woman (Cynthia Ann Parker) who had been captured by Indians at just nine years old and raised as a Comanche. Later in life, Quanah would become the last and most well-known chief in Comanche history.

Adobe Walls was not much to look at, consisting of just two stores, a blacksmith shop and the obligatory saloon. Except for the blacksmith shop, the buildings were wood-framed, sod-sided and sod-roofed. At the time of the raid, 28 men and one woman—the wife of the cook—were on hand. These whites did not yet know it, but they were about to battle a combined force of Comanches, Cheyennes, Kiowas and Arapahos estimated at 250 or more mounted warriors.

The night before the battle was warm and sultry, therefore most of the doors and windows to the buildings had been left open to allow what cool air there was to circulate. Some of the buffalo hunters had even chosen to sleep outdoors rather than with a roof over their heads. Just before dawn on June 27, 1874, Quanah Parker signaled his band to attack. Knowing from spies that the buffalo hunters’ numbers were relatively few, the Indians’ confidence was high.

The pounding hooves of more than 250 war ponies gliding at a gallop across the dry prairie threw a large dust plume high into the air. The buffalo hunters, some of them just awakening, could hear the war cries of the Indians and feel the ground shake from their horses as they quickly approached. Several of the men commented after the battle that the sight of so many war-painted warriors emerging from the east, as if from out of the sun, was one of the most spectacular sights of their life—and probably the most terrifying.

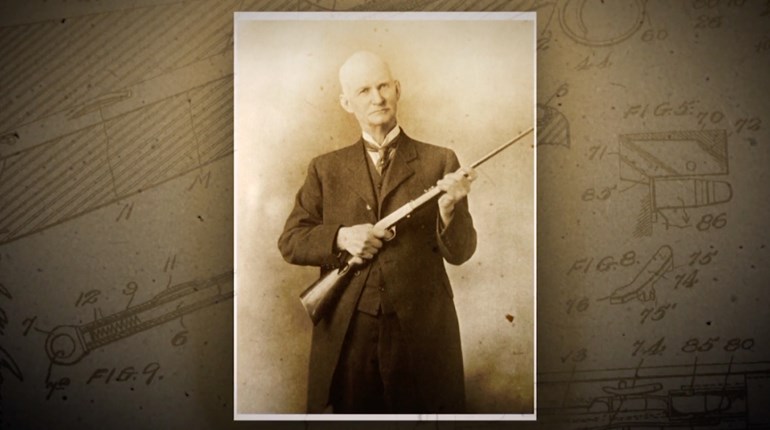

Three of the buffalo hunters were killed and others were wounded during the early stages of the attack, yet, incredibly, the remaining plainsmen were able to hold off the first wave of Indians. The tribes’ warriors’ weapons included both bows and arrows and firearms, mainly repeating lever-action rifles. However, these proved no match for the literal arsenal of weapons and ammunition stockpiled within the trading post. And there was one particular gun that the Indians did not yet know about: the Sharps “Big 50” rifle.

The merchants at Adobe Walls had several cases of these brand-new rifles on hand, plus at least 11,000 rounds of ammunition. Known for their power, range and accuracy, the Big 50s were heavy, single-shot rifles with octagonal 34-inch barrels. Firing .50-caliber cartridges, their bullets weighed 600 grains and were driven by 125 grains of black powder. Powerful enough to knock a one-ton buffalo bull off its feet at 1,000 yards, the Indians’ carbines seemed mere toys by comparison.

Fifteen Indians were killed and many more were wounded. As a result, by mid-morning the remaining warriors had retreated to what they thought was far out of range of the big buffalo guns. It was then that Quanah suddenly had his horse shot out from under him at 500 yards. He quickly took cover, only to be hit by a ricochet, the bullet lodging between his shoulder blade and neck.

Fortunately for Quanah it was not a life-threatening wound, but the fact that their leader was hit had a devastating psychological effect on the Indians—bad medicine. By late afternoon they gave up. Though the Indians remained in the area for several days, taking long-range pot shots at the trading post and anyone who might try to stick his head out, they wisely chose not to attack again.

On the third day following the battle, the buffalo hunter Billy Dixon—a noted marksman—made what has become the most famous long-distance shot in the history of the West. A dozen Indians appeared on a bluff at a distance of some 1,500 yards, almost a mile away.

“Some of the boys suggested that I try the ‘Big 50’ on them,” recalled Dixon. “I took careful aim and pulled the trigger. We saw an Indian fall from his horse.”

The remainder of the Indians fled, and so ended the Second Battle of Adobe Walls.