In 1670, England’s King Charles II granted the fledgling Hudson’s Bay Company a charter and monopoly like none other—control of the lucrative fur trade in the entire watershed of Hudson Bay in North America. That vast region included four million square kilometers, over 40% of what one day would become Canada, as well as a good portion of the future U.S. states of North Dakota and Minnesota.

The extensive area was a combination of forests, swamps, ponds, lakes and streams of all sizes. In essence, it was ideal habitat for the furbearing animals that indigenous peoples had been harvesting for pelts for thousands of years. And the king of those many species, at least economically, was the beaver; an estimated 10 million of the large, aquatic rodents inhabited the area prior to European settlement.

Beavers were in such high demand not simply because their pelts were warm and water resistant. In reality, it was style and fashion that fueled the fur trade, not practicality. Fancy, expensive hats, for both men and women, were all the rage in England and Europe at the time and were manufactured from beaver fur. But first, a beaver had to be captured, either by hunting or trapping.

Various methods were used, such as a primitive cage-like trap baited with the fresh, inner bark of aspen or birch saplings. The trap worked much like a lobster pot; a beaver could easily get in but not easily get out. Large nets were also sometimes employed. Or, the underwater entrances to beaver lodges were blocked with sticks and then that portion of the lodge above the waterline was chopped into with axes and the beavers clubbed and removed.

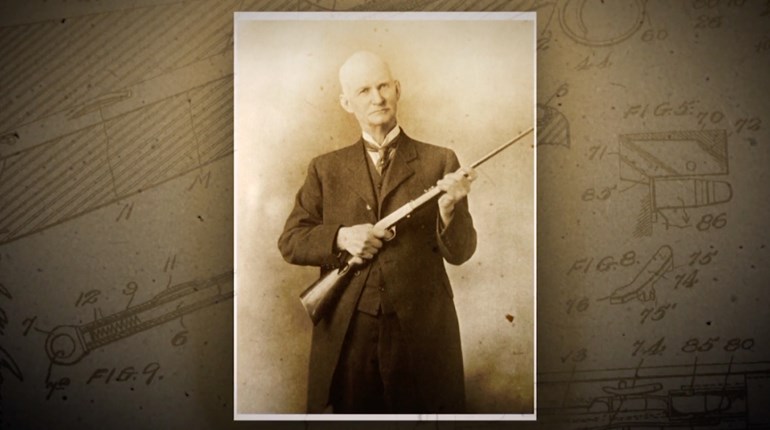

The real game-changer, however, which negated much of that effort, was the steel spring-loaded leg-hold trap, invented by Sewell Newhouse of New York State in 1823. Up to that time, a hardworking indigenous hunter might take a dozen or so beaver per winter. But once equipped with leg-hold traps, a dozen or more beaver could be trapped per day. As a result, the beaver population throughout North America began to decline rapidly.

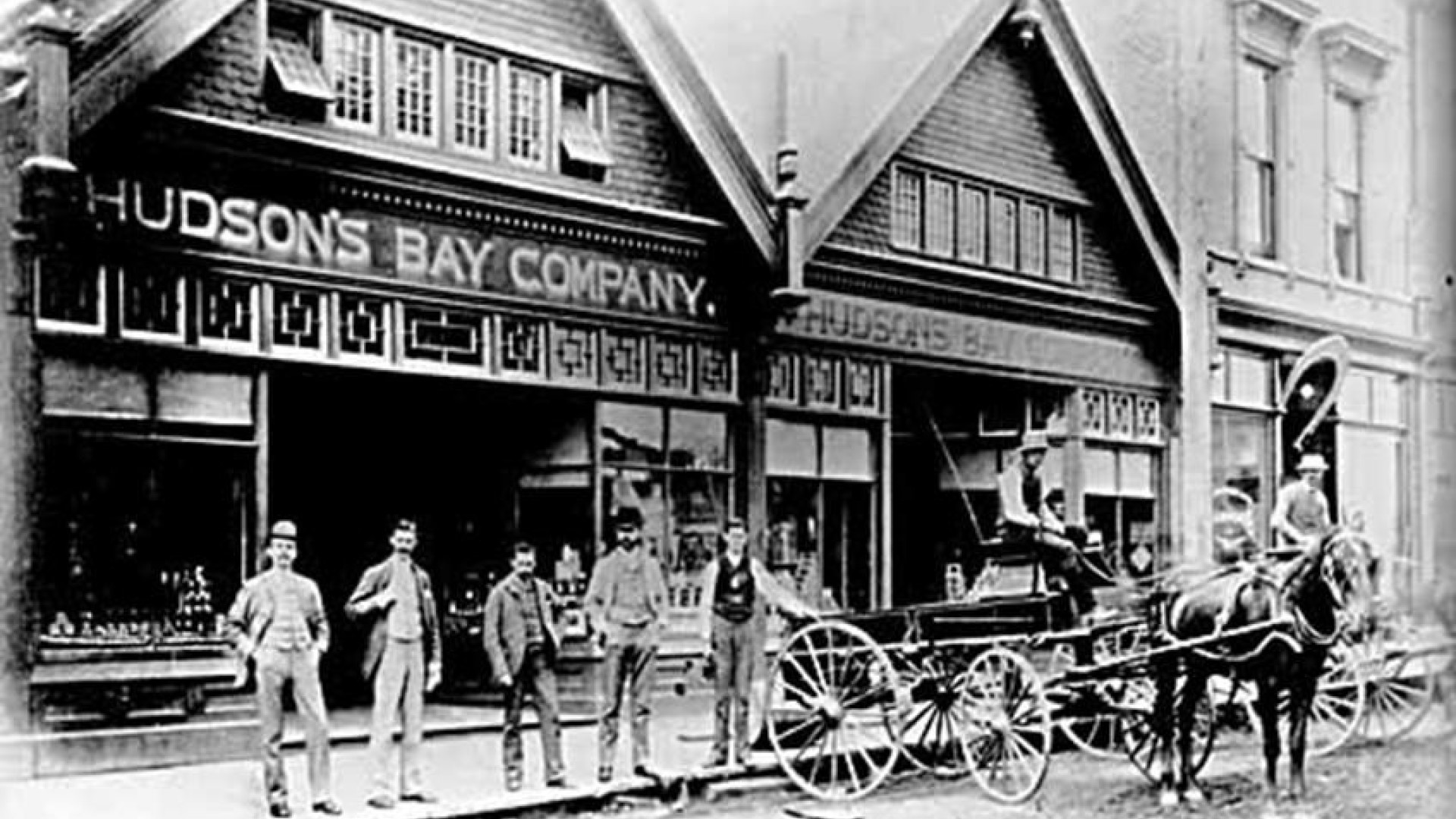

After spending the winter in the bush gathering beaver skins, the time of year when the pelts were most prime, the Indians—mainly Cree—sought out the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trading posts via canoe when the ice began melting in the spring. Half a dozen posts dotted the western shore of Hudson Bay and the southern portion of adjoining James Bay. Early in the history of the Hudson’s Bay Company many of the Indian tribes of North America were still emerging from the Stone Age, so metal objects of any type were highly valued—knives, axes, pots, pans, kettles and, of course, firearms—anything that could help make surviving life in the wilderness easier.

It’s interesting to note that both the Indians and the HBC employees believed they were getting the better part of the trade bargain. For instance, the standard for trading was what came to be known as a “made beaver,” which meant a beaver pelt with the outer guard hairs removed and only the thick underfur remaining. Indians prepared pelts in this manner by simply wearing a beaver skin as a jacket or coat, fur side in, for about a year. During that time, the guard hairs would rub against a person’s body, causing the guard hairs to fall out of the pelt, leaving only the underfur. So, once a jacket or coat was ready to be discarded by the Indians, the pelt was of its highest value to HBC traders. Today, it would be like selling an old jacket for double or more what it was worth when new.

A Jesuit priest, Father Le Jeune, traveling at the time in the bush, said his Indian guide remarked one day jokingly, “The beaver does everything perfectly well, it makes kettles, hatchets, swords, knives, bread … it makes everything. The English have no sense, they give us 20 knives for one beaver skin.”

Once the trading was completed and the Indians were on their way back into the woods for another year of collecting beaver pelts, the next order of business for Hudson’s Bay Company men was preparing for the much-anticipated arrival of the annual supply ships. It took some 10 weeks for a ship to make its way from England to Hudson Bay by sail, and the voyage had to be timed precisely so as to arrive during late summer. If a ship arrived too early or too late, the entrance to the bay, Hudson Strait, could be blocked by sea ice.

Upon arrival, the post’s trade goods for the coming year were unloaded and the waiting bales of furs crammed into the ship’s hold. All this work was done as quickly as possible, as no ship captain or crew wanted to be hemmed in by ice and have to spend a long, dark, bitterly cold, six-month winter on the bleak shores of Hudson Bay. Once back in England, the valuable cargo of furs was unloaded and auctioned, the beaver ultimately sold to the hat makers who would turn them into those much-sought-after felt hats.

“In general,” writes Stephen R. Bown, author of The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire, “the waterproof and durable beaver felt hat … was perfectly suited to symbolize and reflect the desires of an increasingly stratified and mercenary society. People were marked by their hats, the prices of which were well known and appreciated. Since it took about three to four worn beaver pelts to make enough felt for a single hat, some hats were so pricey that they were carefully tended and repaired for years and then passed down as inheritances. Even wealthy people kept inferior spares to be worn in inclement weather, saving their best beaver for notable occasions—or at least occasions when others might note the quality and make of the hat.”

But beaver hats had a hidden health cost, particularly to the professional hat makers. Beaver felt was made by using a combination of heat, moisture, pressure and mercury nitrate to shrink the fur fibers so that they matted together. Hatters, during their careers, spent years inadvertently inhaling the mercurial fumes as they worked, not realizing that those fumes would lead to a type of poisoning called erethism or “mad hatter disease,” the symptoms of which included tremors, depression, delirium, memory loss and hallucinations. Unfortunately, the Mad Hatter was not just a crazy character in Lewis Carroll’s 1865 children’s book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; they really existed.

In 1870, exactly 200 years after the Hudson’s Bay Company received its original charter and monopoly, it surrendered its land rights to the British Crown, which in turn transferred them to the new nation of the Dominion of Canada. However, the Hudson’s Bay Company continues in operation yet today as a chain of retail department stores in Canada, the oldest and longest-surviving company in North America, as well as one of the oldest and largest continuously operating companies in the world.

One of the modern Company’s most famous and popular products, a throwback to the fur trade, is the Hudson’s Bay point blanket. Made of heavy wool, the blanket has traditional single stripes of green, red, yellow and blue on a white background. In addition, four short black stripes or “points” are woven into the wool. A misconception is that the points originally indicated the number of beaver pelts required in trade for a blanket. Rather, they designate the overall size of a blanket. Regardless, you can’t trade a beaver pelt for a Hudson’s Bay point blanket today—it's either cash or charge.