Arizona, 1913

The grizzly was a big one-maybe the biggest he'd ever tracked. And it was most certainly well fed. It had been feasting on the local cattle for going on four years, despite the best efforts of the local ranchers to kill it or drive it off.

“But you're dealing with Ben Lilly, now,” he thought to himself. “So don't get to feeling too comfortable out there, you old varmint.”

The bruin was wounded. He'd managed to hit it three times in three days, but the shots were all long-distance and hadn't seemed to slow it down much. And now, the man thought, the pain had made it one angry bear.

His dog, tethered to his waist by a thick rope, growled deep in its throat. Suddenly, the bear charged out from the dense undergrowth just 15 feet in front of him. The man quickly swung his rifle to his shoulder, getting off two shots, one to the upper body and one to the head, before the bear was upon him.

With the action now up close and personal, the man reached for his knife and plunged it deep into the bear's heart-and the fight was over.

Breathing heavily, the man reached out to quiet his excited dog. “Phew,” he managed. “That was close, wasn't it, partner?”

*************************

Ben Lilly was born in Alabama in 1856 and spent most of his childhood in Mississippi. When he was 12, his parents sent him to a military academy. But the regimented life of a military school was not for the free-spirited Lilly, and it wasn't long before he ran away. In fact, for much of Lilly's teenage years, his family had no idea where he was.

Lilly's uncle Vernon, a wealthy landowner, eventually discovered young Ben's whereabouts while on a business trip to Memphis, Tenn. There, he found Lilly running a blacksmith shop and talked him into returning to Mississippi to work on his farm. A few years later, upon his uncle's death, Lilly inherited the property.

Although Lilly worked hard at farming, he took to the life of a landowner no more than he had taken to military school-or to married life, for that matter. Lilly actually married twice and had several kids, but he preferred life in the wild, sleeping on the ground (or in trees, if need be), hunting daily and being in close contact with nature rather than people.

Lilly was known for his strength and general fitness. Just 5 feet, 9 inches tall and 180 pounds, he could, nevertheless, lift and carry a 500-pound cotton bale on his back. His running skills left nothing to be desired, either. He once challenged a local athlete to a race around a baseball diamond, betting he was quicker on all fours than the other man was on two feet. Sure enough, Lilly crossed home plate a half-base ahead of his competitor.

He was an honest, well-spoken man who didn't drink alcohol or coffee, didn't smoke or curse and never worked on Sundays. Whether the cows got out or he was hot on the trail of an animal, Sunday was for Bible reading-so corralling those escaped cows or bringing in the animal he treed on Saturday had to wait for Monday.

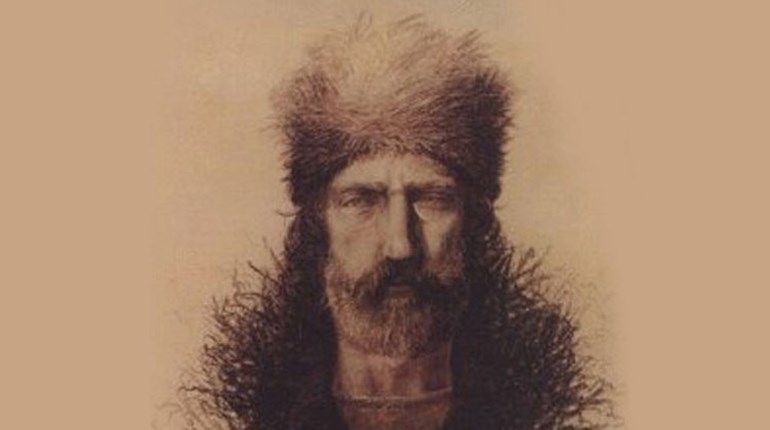

Lilly was also known for having some strange ideas. Take his long beard, for instance. He claimed that as a boy, the first time he saw a clean-shaven man he was frightened and believed he was looking at a dead man walking. As a result, he vowed he'd always wear a beard so he wouldn't scare anyone into thinking he was a corpse.

Then there was his need for solitude. Lilly was fond of putting an ear of corn in his pocket, grabbing his blanket and his rifle, and heading into the woods for days on end, hunting to his heart's content and leaving his family to guess when he'd return.

One day, his wife pointed to a hawk perched in a nearby tree and complained that it had been getting after the chickens. Lilly picked up his rifle and headed outside, but as he raised the gun to his shoulder, the hawk took off. So did Lilly, who did not return home for more than a year. “That hawk just kept flying,” he said by way of explanation.

Eventually, one story goes, Lilly's put-upon wife had enough of his lengthy and often unexpected absences and issued an ultimatum-something along the lines of “next time you leave on a hunt, don't come back.” So Lilly transferred all his property into his wife's name and left the solid walls of a home behind forever. He did, however, continue providing for his children, writing and sending money to them over the course of the next 30 years.

Lilly moved on to the southwestern United States and Mexico. For a time, he tried the pig trade and logging, but he eventually settled into doing what he did best-hunting.

Lilly guided Theodore Roosevelt on a hunting trip in Louisiana. As his superior hunting skills became known, he was hired to collect and send in specimens to the U.S. Biological Survey, which would later become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. These specimens helped scientists identify species that were unique to the American Southwest. Several of Lilly's contributions, including a male grizzly he killed in Arizona, remain in the collection of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

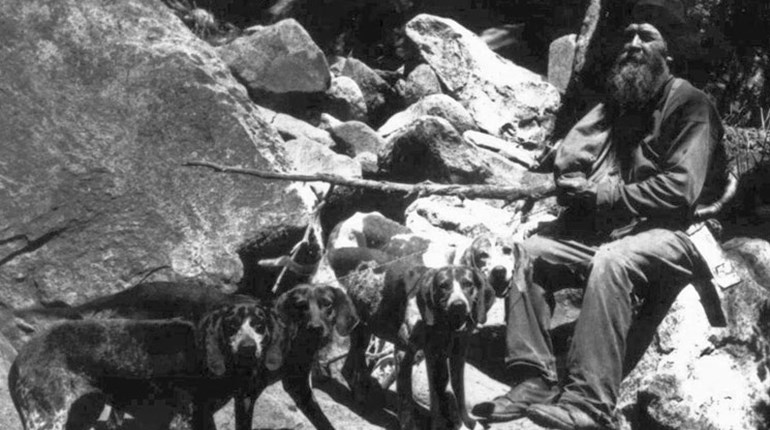

Hunting was Lilly's passion. Between the ages of 50 and 70, he hunted every day of the week except Sunday. By 55, his passion had made him a well-paid professional hunter, thanks to the large predators that had become a problem for cattle ranches.

In fact, a single grizzly might kill several hundred dollars' worth of cattle a year. So the Federal government began offering bounties for bears that were “proven cattle killers,” and wealthy ranchers often hired their own trackers. Lilly became a very busy man, indeed.

Although the ranchers who hired him usually provided bed and board, Lilly preferred to set up camp nearby. His needs were few: a couple of hunting rifles, ammunition, a tin can for cooking, matches, an ax, a blanket and tarp, a couple of self-made knives (one for killing, one for skinning), a blowing horn to call his dogs and dog tethers.

For food, he carried along only some dried corn or cornmeal and a little sugar, preferring not to eat while tracking. Once he made the kill, he feasted on the newly harvested animal.

By the time he reached his late 70s, Lilly was forced to give up the outdoor life he loved. His final days were spent on a ranch near Silver City, N.M., where he passed away in bed at age 80.

Epilogue

No one really knows how many predators Ben Lilly brought down over the course of his life. Perhaps the best estimate comes from Lilly expert and author M.L. “Dutch” Salmon, who suggests the extraordinary hunter killed some 600 mountain lions and over 500 bears. By any standards, that's a remarkable feat!