He’d already won the first shooting contest—hit the dead center of the bullseye at 100 yards. Even Little Rock’s best marksman had fallen to his superior shooting. “A chance shot,” someone muttered.

“Chance nothing,” he thought to himself. “I shoot like this five times out of six.”

And so it was that Davy Crockett found himself in a second competition with the good folks of the town of Little Rock. He raised “Old Betsy” to his shoulder and gently squeezed the trigger. Cr-a-a-ack!

“It’s a miss,” shouted someone in the crowd. By now, competitors and spectators alike had gathered round to inspect the target. “It’s a dead miss,” crowed another. Clearly, they thought, this visitor’s skill as a marksman had been overrated.

“No way,” thought Davy. He stepped forward to examine the target for himself, working his way carefully from top to bottom. Finally he focused on the bull’s eye, letting his finger trace the edges of the bullet hole from his earlier shot. Bingo. He allowed himself but a small smile before explaining to the crowd that his second shot had followed in the exact tracks of his first.

“That’s impossible,” said one of the marksman. “Couldn’t happen,” said another.

“Tell you what,” said Davy, “search the hole. If you don’t find two bullets, you can use me as the target for the next round.” So search they did, only to find two bullets, one behind the other—exactly as Davy had said.

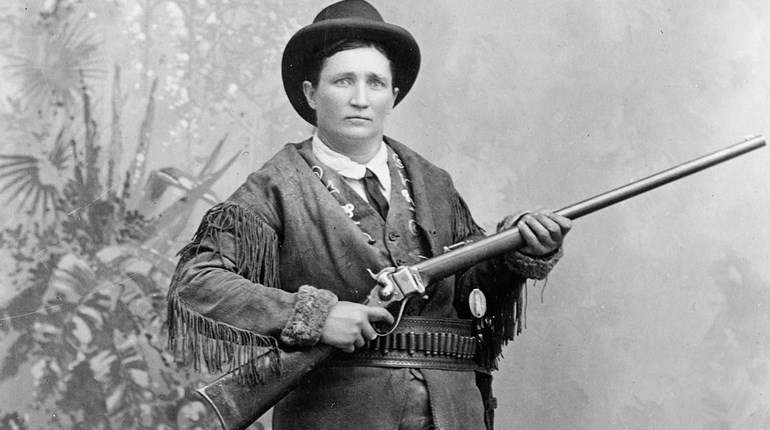

David Crockett, or Davy as he was called, was an extraordinary marksman, a hunter, a trapper, a frontiersman, a soldier, a state legislator and a congressman. He was also a folk hero.

Born in 1786 in East Tennessee, Davy was one of nine children. As a boy he worked in his father’s tavern, a waypoint for wagon trains heading from Virginia to Knoxville, Tenn., and points west.

When Davy was 12, his father hired him out to a cattle drover. The young Crockett was to help herd the cattle to Rockbridge County, Va., some 300 miles distant. But at journey’s end, the drover tried to force Davy to stay. Under cover of darkness and a blinding snowstorm, he eventually escaped and made his way back home, only to leave again the following year rather than face a whipping for playing hooky from school. This time he stayed away until he was almost 16.

The Making of a Man

When he returned, Davy took on his father’s debts, working for a year to pay off $76—a lot of money in those days. He continued working the job for six more months in exchange for six months of schooling. Then, able to sign his name, read at a basic level and do simple math problems, the young man was ready to make his own way in the world.

In 1806, 19-year-old Davy married Polly Finley. Seven years later, with his wife and sons settled in middle Tennessee, he heard that the Creek Indians had massacred some settlers at Fort Mims in Alabama. This prompted him to join the Army, where he was a scout under General Andrew Jackson in the Creek War.

By 1821, Davy’s first wife had passed away and he had remarried. During this period he was elected a colonel in the state’s militia. Despite his lack of schooling, Davy was an intelligent man with a concern for others, and he had a knack for telling jokes and stories, characteristics that made him very popular. He was elected to the Tennessee state legislature and, later, to Congress.

Davy loved to hunt bear. Armed with his Bowie knife and his trusty musket, “Old Betsy,” he would head out with his sons, a friend or by himself in search of his favorite prey. Stories of Davy’s bear-hunting adventures spread far and wide—in his books as well as in books written about him.

In 1835, he was defeated for re-election to Congress and moved to Texas, which at that time was trying to win independence from Mexico. Davy joined a group of volunteers based in San Antonio to support the cause.

The Alamo

By early the next year, General Sam Houston and the American troops had withdrawn from the area. A small cadre of less than 200 men, including Davy, retreated to the Alamo to defend it against a Mexican force of nearly 5,000 troops commanded by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

The Alamo was shelled for 12 days, then stormed. Davy and the other defenders fought until they ran out of ammunition. They all perished, but not before they had taken down 1,600 of the invading Mexican army. The war continued without them, but “Remember the Alamo” became the battle cry as American soldiers ultimately defeated Santa Anna, winning independence for Texas.

Postscript

Davy Crockett penned his motto on the title page of his 1834 autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee: “Be always sure you’re right—then go ahead.” It is surely a motto fit for a hero.