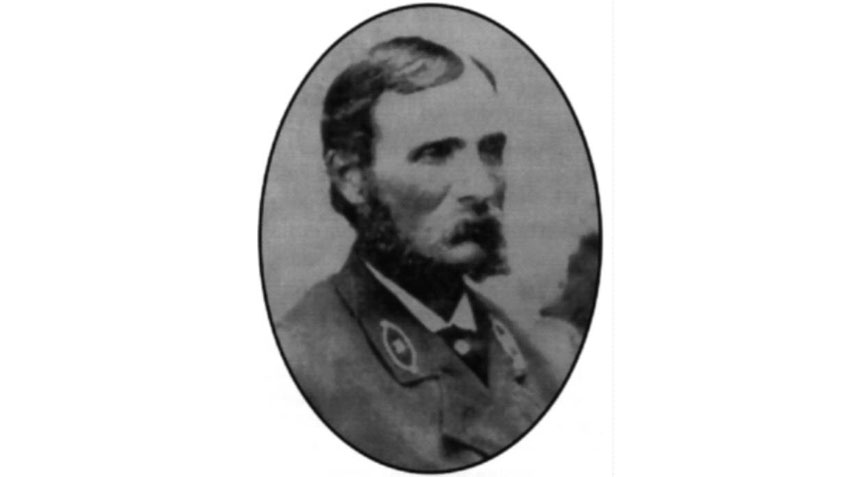

In all of American history, only one person—Marcus A. Hanna (1842-1921)—has ever received both the Congressional Medal of Honor and its civilian counterpart, the gold Lifesaving Medal. The first medal he received for his heroic actions during the Civil War; the second as a result of his activities as, of all things, a lighthouse keeper. The following are his two stories of heroism, during either of which he easily could have lost his life.

During the American Civil War, Hanna was a sergeant in Company B of the Fiftieth Massachusetts Infantry, a Union unit that from late May to early July 1863 had been helping lay siege to a Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson, Louisiana. On July 4, Independence Day, his unit was ordered to occupy a rifle pit in support of a battery of Union soldiers from New York. A rifle pit is a shallow trench that provides cover for infantry while firing on the enemy.

Hanna’s unit had already seen action earlier in the day, so had not had time to refill their canteens before entering the pit. July days in Louisiana are sweltering, especially in direct sunlight, so it was not long before the soldiers of Company B were out of water and becoming severely dehydrated. As a result, Hanna asked permission of his lieutenant to make a water run, and permission was granted. The nearest spring, however, was 500 yards away—the length of five football fields—and the enemy along the route controlled the high ground. Anyone crossing that long, open distance would be taking his life in his hands, yet Hanna chose to go.

When he asked for volunteers to accompany him none of his men stepped forward, realizing the extreme danger. Undeterred, Hanna took his platoon’s 15 empty canteens, draped their carrying straps over his shoulders, and began racing toward the spring. Despite the hail of bullets whizzing past and kicking up dirt at his feet, Hanna made it to the spring and back unscathed…Confederate sharpshooters no doubt cursing his good luck.

Twenty-two years later, at age 43, Marcus Hanna’s good fortune would continue, but just barely. By then, he was head lighthouse keeper at the Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse in Maine, a profession he came to naturally, as both his father and grandfather had been lighthouse keepers before him. In those days, lighthouse attendants were not only expected to keep their light burning at all costs during nighttime hours, but also to attempt rescue of people in case of shipwreck.

Such a wreck occurred in late January 1885 during a monster snowstorm in the North Atlantic. Caught in that storm was the schooner Australia, being sailed by a three-man crew consisting of the ship’s captain, J.W. Lewis, and two sailors, Irving Pierce and William Kellar.

The howling winds had shredded the ship’s sails, so the captain decided that their only chance for survival was to intentionally drive the ship onto the rocky shore and hope for the best in the pounding surf. As luck would have it, the ship was just off the Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse. Lewis spun his ship’s wheel toward the light and fog signal—and prayed.

Marcus Hanna had just been relieved from the midnight to six a.m. shift by his assistant keeper and, nursing a bad head cold, wanted nothing more than to go to bed. But he hadn’t slept long when his wife threw open the bedroom door and announced, “There’s a vessel ashore!” Now instantly awake, Hanna threw on his coat, hat and boots, and ran outside into the deep-drifting snow. Of the storm, Hanna would later say it was, “one of the coldest and most violent storms of snow, wind, and vapor” he personally had ever experienced.

By the time Hanna got to the Australia, Pierce and Kellar had climbed into the fore rigging and were holding on the best they could despite the minus-10-degree temperature and brutal wind. Captain Lewis had been washed overboard when the ship stranded--his body was found along the rugged shore days later.

Hanna knew he could not effect a rescue of the two remaining seamen by boat in the crashing surf. He got a rope, tied a lead weight to one end, then crawled over ice-covered rocks to get closer to the stranded ship. Time and again he threw the rope toward the boat, only to have the lead weight land just short of the deck. It was then that Providence stepped in. A giant wave picked up the entire ship and moved it a few yards closer to shore. Hanna said, “She came down with a thunderous crash, staving in her whole port side [and] careening her on her beam ends.”

Wading deep into the icy water, Hanna tried again and this time the rope hit its mark. The two sailors tied the rope around Pierce’s waist and Hanna hauled him to shore, hand over hand. He then threw the rope to Kellar, but Hanna, now hypothermic himself, had no strength left to pull Kellar to safety. Thankfully, it was about that time help arrived in the form of three neighbors who had spotted the wreck and come to assist. Only a short time later, once everyone was out of the water and safely on shore, a towering wave hit the Australia, completely destroying her.

The Congressional Medal of Honor is America’s highest and most prestigious personal military decoration, awarded in recognition of U.S. military service members who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. The gold Lifesaving Medal, today issued by the United States Coast Guard, is one of our nation’s oldest medals. Marcus A. Hanna was worthy of both.