Considered one of the Four Great Inventions of ancient China, gunpowder was first used in warfare around the year 1004 AD. Since then, firearms technology has advanced more or less steadily through the years, but many of today’s shooters don’t realize that it was often new or improved ammunition, not necessarily new long guns and handguns, that triggered the technological developments of the past millennium. Such was the case with the Minié ball bullet.

Invented in 1849 by the French army captain Claude-Etienne Minié, the Minié ball, as it came to be known, was a vast improvement over the standard, round lead-ball bullets used in muzzleloading long guns of the time. However, the name Minié ball is somewhat confusing. First of all, Minié in French is pronounced Min-A, not Minnie. (That said, most American gun enthusiasts pronounce it “Minnie.”) And secondly, the bullet was not a round ball. Rather it was cone-shaped, making the bullet more aerodynamic in flight; as a result, more accurate and deadly on the battlefield, especially at longer ranges.

The Minié ball was unique in design in that it was not only cone-shaped, much like a modern rifle bullet, but it also had a hollow base, allowing the soft lead of its rearward “skirt” to expand slightly when the gun was fired. This, in turn, better sealed off the gasses produced by the burning gunpowder, producing more power, more velocity and longer distances for the bullet. In addition, two to four grooves were cut around the base of most Minié balls, making them more stable in flight.

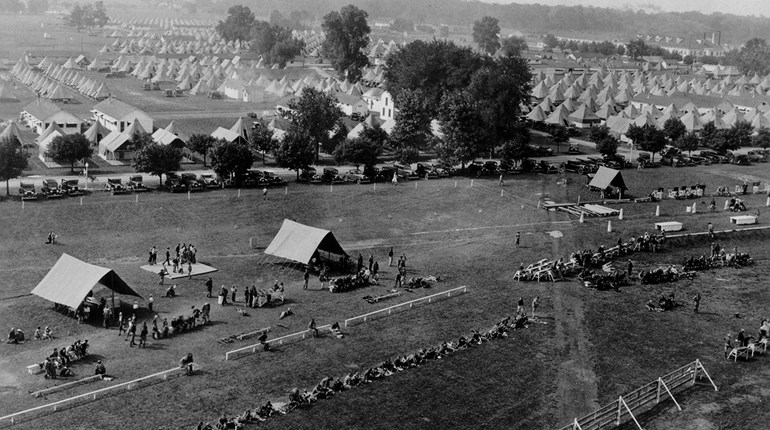

Because of their expanding skirts, Minié balls could be cast slightly smaller in diameter than the diameter of the gun barrels they were used in, making the bullets easier to force down a barrel with a ramrod when loading. This was a decided advantage during combat. Standard round balls were difficult to ram down a barrel, especially when firing repeatedly. Civil War soldiers were trained to load and fire as fast as three shots per minute, and as a result muzzleloader barrels quickly became fouled with black powder residue and also swelled from the heat of repeated shots. Both armies, North and South, fired Minié balls during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

In 1855, several years prior to the start of the war, the United States Army adopted the Minié ball and the rifled musket as weapons. The first U.S. rifled musket to use the Minié ball bullet was the .58-caliber Model 1855 Springfield. Another popular rifled musket was the .69-caliber Harpers Ferry. Ironically, Jefferson Davis was Secretary of War at the time the guns were officially adopted. Yes, the same Jefferson Davis who in a few years would lead the Confederacy in rebellion against the Union.

The effective range of a rifled musket was 300 yards or more, but the effective range of a smoothbore musket was just 50 to 200 yards--if that. When the Civil War began, both sides were using older, outdated smoothbore muskets. As the war progressed, the new rifled muskets loaded with the Minié ball replaced the smoothbores.

The new weaponry made many generals and field commanders begin to rethink their battlefield tactics. Would the increased range of the Minié ball dictate more long-range warfare? It didn’t turn out that way. Even though Minié balls could travel half a mile, rifled muskets could not take full advantage of this increased range because of the bullet’s steep trajectory.

In essence, the Minié ball’s trajectory created two effective zones, the first from zero to 100 yards, and the second from about 250 yards to 350 yards. Between those two zones enemy soldiers were relatively safe, as the Minié balls flew over their heads. Sharpshooters firing Minié balls learned to compensate for the high trajectory through training, but the average Civil War soldier received little instruction and target practice, especially as the war wore on.

Where the Minié ball’s impact was most felt—literally—was in the severity of the wounds it inflicted. Because of its higher velocity and mass compared to round lead bullets, the Minié ball tended to shatter bones, producing ghastly compound fractures. Given the state of field medicine at the time, amputation of a limb was often the only option. Following Civil War battles, a grisly pile of amputated arms and legs was common outside a surgeon’s tent. In fact, it is believed that the Minié ball was responsible for the majority of Civil War combat casualties, with amputations amounting to three-quarters of the surgeries performed.

By the way, if you were wondering what the other three of the Four Great Inventions of ancient China were in addition to gunpowder, they were papermaking, printing and the compass.