In his book, The Horn of the Hunter: The Story of an African Safari, Robert Ruark recalls a boyhood dream of writing a story about quail hunting with his dogs and seeing it published in a glossy magazine. As he grew a little older and read books about Africa, hunting and travel, his dreams expanded until, "... It seemed I would bust a gusset if I didn't get to see jungles and lions and cannibals someday."For many, the dreams of their youth are tossed aside or long forgotten by the time they reach adulthood. For writer and big-game hunter Robert Ruark, those early dreams were just the beginning.

Childhood

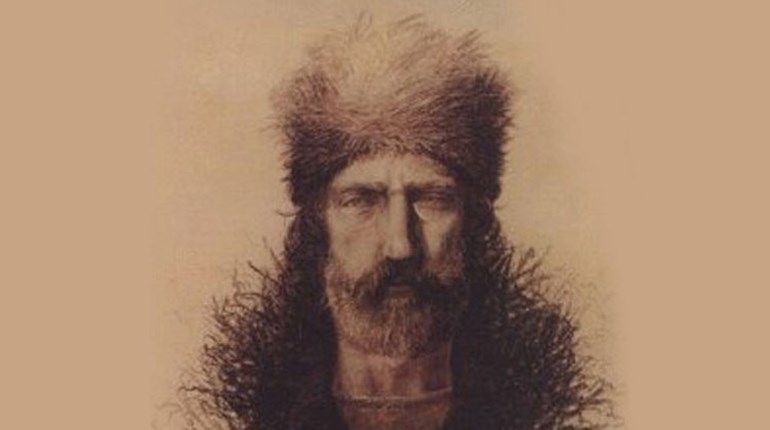

Robert Chester Ruark, Jr., was born on December 29, 1915, in Wilmington, N.C., to bookkeeper Robert, Sr., and his mother, Charlotte. Young Ruark was particularly close to his maternal grandfather, Edward Atkins, and spent his summers and whatever other times he could manage at his grandfather's Southport, N.C., home.

Adkins, a former river pilot, was equally devoted to his grandson. The two spent hours together in the outdoors, the old man teaching the young boy about hunting, fishing and sportsmanship. He also passed on a love of reading and a desire to travel.

Ruark was a studious boy who did well in school-so well, in fact, that he graduated early from high school and began his college days at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill when he was only 15. His major was journalism.

Career Start

Ruark started his professional career with jobs at a couple of small North Carolina newspapers, the Hamlet News Messenger and the Sanford Herald. It wasn't long before he decided to move to Washington, D.C., taking a job as an accountant for the Works Progress Administration. The job was not exactly a good fit, but a position at the Washington Daily News was. Ruark started as a copy boy and worked his way up to sportswriter and, eventually, columnist.

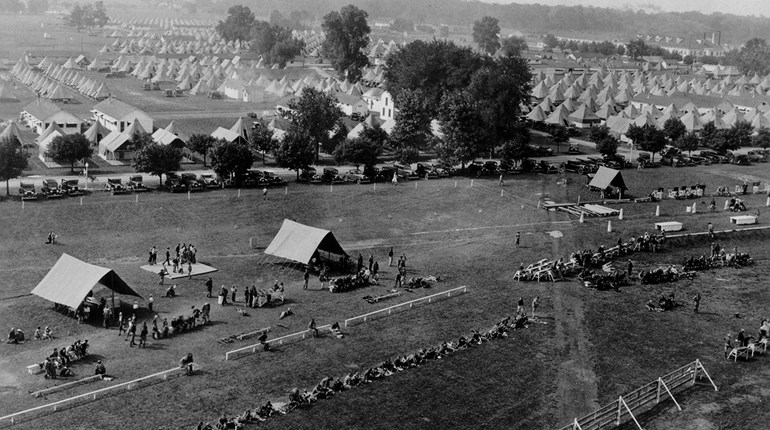

During World War II, Ruark served as a gunnery officer in the U.S. Navy, following which he returned to the Washington Daily News as a columnist. Eventually, some of his writings from this period were turned into books: I Didn't Know It Was Loaded in 1948 and One For the Road in 1949.

But Ruark didn't just write columns. As he became more well known, he turned his hand to writing short stories, novels (Grenadine's Etching in 1947 and Grenadine's Spawn in 1952) and articles and novels for magazines, among them the Saturday Evening Post, True and Esquire.

Africa at Last

Once established in his career, Ruark decided the timing was right to fulfill his boyhood dream of seeing "jungles and lions and cannibals." So in the early 1950s, he did just that. His book, Horn of the Hunter: The Story of An African Hunt, which was published in 1953, records the details of his first safari. It would not be his last.

In fact, Ruark moved to Africa, where he undertook multiple safaris. The country, the people and the animals provided him with material for a number of his works, including his first best-selling novel Something of Value, which was published in 1955, and the one-hour documentary film African Adventure, which Ruark wrote, directed and narrated.

During this same period, starting in 1953, Ruark began writing a column for Field & Stream magazine entitled The Old Man and the Boy. The series was about a young boy growing up in coastal North Carolina and the wise and loving grandfather who taught him how to hunt, fish and train dogs. Although written as fiction, the works are considered autographical-or mostly autobiographical.

A novel, The Old Man and the Boy, published in 1957, is a compilation of those columns. A follow-on novel, The Old Man's Boy Grows Older, published in 1961, includes additional columns in the series, which ran until late 1961.

In a chapter from The Old Man and the Boy, the Old Man talks to the young boy about how to shoot quail. The boy listens carefully, takes his gun and walks past his bird dog and, when the birds flush, fires often and randomly, hitting nothing.

Mortified, he looks at his grandfather. The Old Man reassures the boy that he, too, had missed plenty of shots over the years and would continue to miss occasionally as long as he kept shooting. But, he continues gently, "Nobody can kill the whole covey-not even if they shoot the birds on the ground running down a row in a cornfield. You got to shoot them one at a time."

The Last Years

In 1957 Ruark paid one last visit to the U.S. and his hometown of Wilmington, N.C., before moving overseas permanently, where he had homes in Spain and England. There, he continued to write, though his later works did not have the same success as his earlier efforts. He died of liver disease in 1965 at just 49 years of age and was buried in Palamos, Spain.

Ruark's life was short and not altogether happy. He had a rocky relationship with his parents, his marriage to interior designer Virginia Webb ended in divorce after 25 years, he was an alcoholic and, as a loner, he had few friends. He did, however, achieve his early dreams of becoming a successful writer and traveling to far-off lands, including Africa, where he lived for a number of years. He was also known as a skilled hunter of big game. In 2009, Ruark was inducted into the North Carolina Journalism Hall of Fame.