During the late 1800s on the Great Plains of North America, people living east of the Mississippi and traveling westward on the new transcontinental railroad felt they were not truly in wild country until they encountered their first buffalo. In the summer of 1870, 20-year-old George Bird Grinnell was one of those people, as the train he was riding in screeched to a sudden stop due to the rails ahead being blocked by buffalo. “We supposed they would soon pass by,” Grinnell later wrote, “but they kept coming … in numbers so great they could not be computed.” It took more than three hours for that particular herd to cross the railroad tracks and the train to proceed.

George Bird Grinnell was born into wealth and privilege in 1849 in Brooklyn, New York, the first of five children of George Blake Grinnell and his wife, Helen. George, the father, was the principal Wall Street agent of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. Young George would likely follow his father into the world of finance one day, but all those expectations began to change when the family moved to a country home outside of Manhattan when the boy was just seven.

The neighborhood was known as Audubon Park, because the land was once owned by the accomplished bird painter John James Audubon and his family. The famous naturalist had been dead six years when the Grinnells arrived, but Audubon’s elderly wife, Lucy, was still alive and active. She loved the neighborhood children and they loved her, affectionately calling her “Grandma Audubon.” Young Grinnell learned to hunt and fish from the boys living in the area, but it was at Lucy Audubon’s knee that he learned a deeper appreciation for the natural world … particularly concerning birds, unsurprisingly.

Grinnell’s next early mentor was Othniel Charles Marsh, a professor at Yale. Grinnell had been studying at the university for several years, and was close to graduating, when he heard that Marsh was planning a scientific expedition to the West to collect dinosaur bones. It was rumored that Marsh was looking for a few students to join him, and Grinnell jumped at the chance, asking Marsh to take him along.

It was during this 6,000-mile, five-month trip that the expedition’s train was stopped by the aforementioned buffalo herd crossing the railroad tracks. It was those buffalo and the subsequent adventures on the expedition that would change the course of George Bird Grinnell’s life. In essence, the experiences would ignite a love affair within him for the West, its wildlife, wild places and indigenous peoples that would endure until the end of his life in 1938.

During future expeditions west, Grinnell met such frontier celebrities as William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and General George Armstrong Custer. Grinnell even rode with Custer and his army as an accompanying scientist during their 1874 expedition to the Black Hills in search of gold. Grinnell wrote, “Gen. Custer was a man of great energy. Reveille was usually sounded at 4 o’clock, breakfast was ready at 4:30; and by five tents were down and wagons packed, and the command was on the march. Camp was not reached until 8 o’clock at night, sometimes not till midnight, and sometimes not at all.”

Custer was so impressed by Grinnell that he invited the young man along again two years later, in 1876. But Professor Marsh advised Grinnell not to go, stating there would probably not be sufficient time for scientific exploration during the proposed expedition. That prescient advice likely saved Grinnell’s life.

“Had I gone with Custer I should in all probability have been mixed up in the Custer battle, for I should have been either with Custer’s command, or with that of Reno, and would have been right on the ground when the Seventh Cavalry was wiped out.”

In addition to Grinnell’s growing taste for adventure, there was nothing he enjoyed more than hunting, buffalo included. In fact, he had the good fortune of experiencing the very last buffalo hunt of the Pawnee, an Indian tribe peaceful toward whites. The Pawnee had already been subjugated and were living on a reservation, but the U.S. Army allowed them to leave twice annually for a few weeks to hunt buffalo.

It was always a time of celebration for the tribe, a time of following the old ways, and Grinnell was invited along. However, a year later while once again on their Kansas hunting grounds, the Pawnee were attacked by their enemy, the Sioux. The number of Pawnees killed was 156 men, women and children. As a result, the Pawnees never hunted buffalos again.

That same year, 1873, Grinnell published an account of his hunt with the Pawnee in the weekly national outdoors magazine Forest & Stream. In it, he included this candid, foresighted thought about the future of the buffalo as a species.

“Their days are numbered,” Grinnell wrote, “and unless some action on this subject is speedily taken not only by the states and territories, but by the National Government, these shaggy brown beasts, these cattle upon a thousand hills, will ere long be among the things of the past.”

Within several years, George Bird Grinnell would become the natural-history editor of Forest & Stream, then take over as editor in 1881, a position he would hold for three decades. Under his tutelage, the magazine would become a national public pulpit he would use to its fullest extent in fighting for the fate of the buffalo. He wrote dozens and dozens of scathing editorials condemning market hunting—which was legal at the time—alternately cajoling and chastising the federal government to do something to stop it. In addition, he encouraged sport hunters to contact members of Congress and do the same.

Grinnell even went so far as to begin prowling the halls of Congress, lobbying whoever would listen. “It was the meanest work I ever did,” he wrote in a letter to a friend. “I would rather break broncos for a living than talk to Congressmen about a bill.”

What Grinnell opposed most vehemently was the slaughter of buffalo for their hides and tongues by professional hunters, the meat left to rot, hundreds of pounds of it per animal. Market hunters did not act alone, but in teams of half a dozen or more men. One or two did the actual shooting, which kept several men busy skinning, while others remained at camp cooking and staking out buffalo hides to dry.

A market hunter would stalk slowly upwind within range of a buffalo herd, usually getting within 200 to 300 yards, then settle in to study the individual animals, attempting to determine which one was the lead cow. Once she was identified, shot and killed, the remaining buffalo were reluctant to leave her—the technique was called “tranquilizing” or “mesmerizing” the herd—and the rest of the cows and bulls were then systematically shot down one at a time. Using this method, market hunters could kill dozens of buffalo per day, if not half a hundred or more. Kills exceeding 100 buffalo per day were not uncommon.

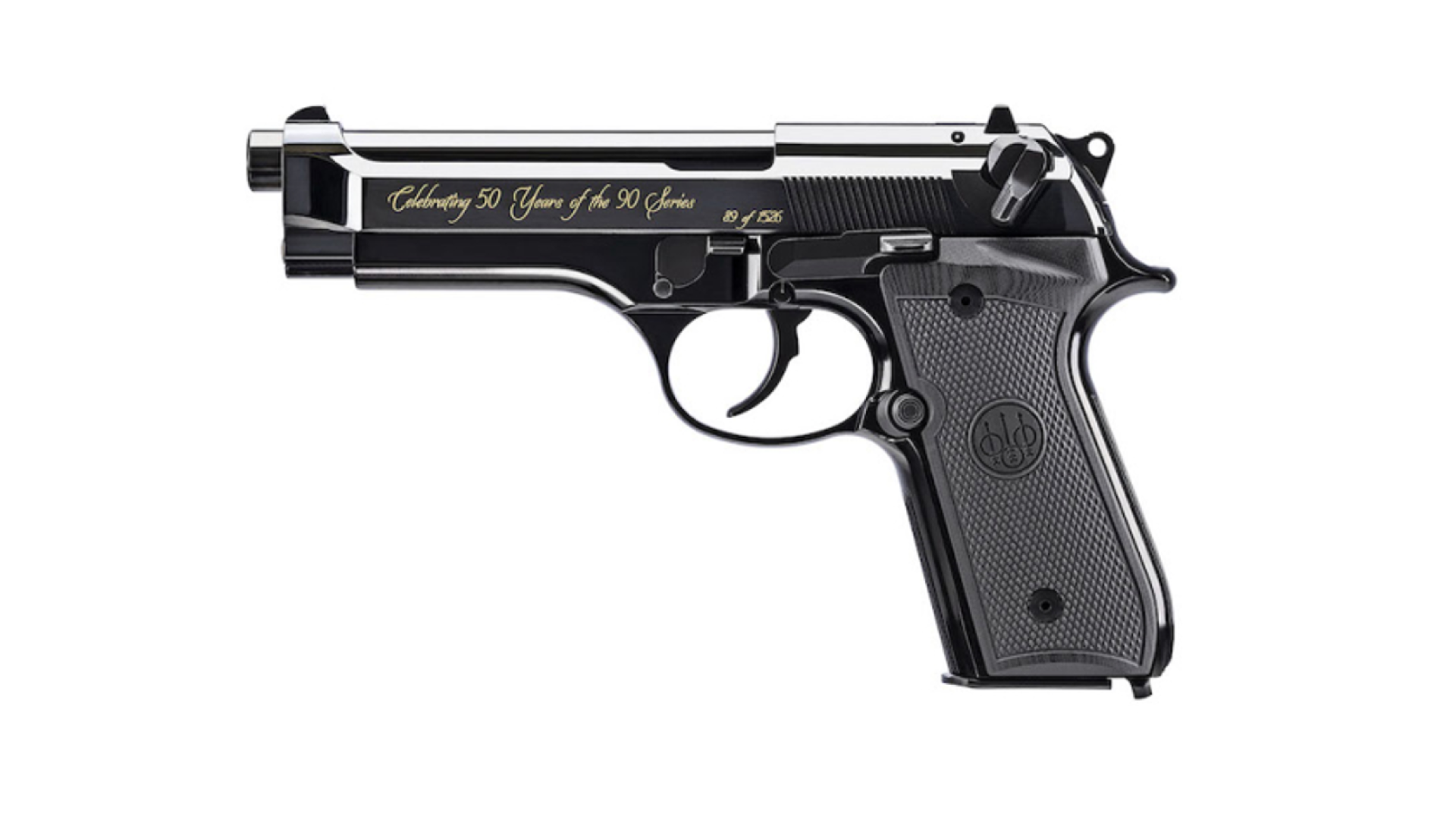

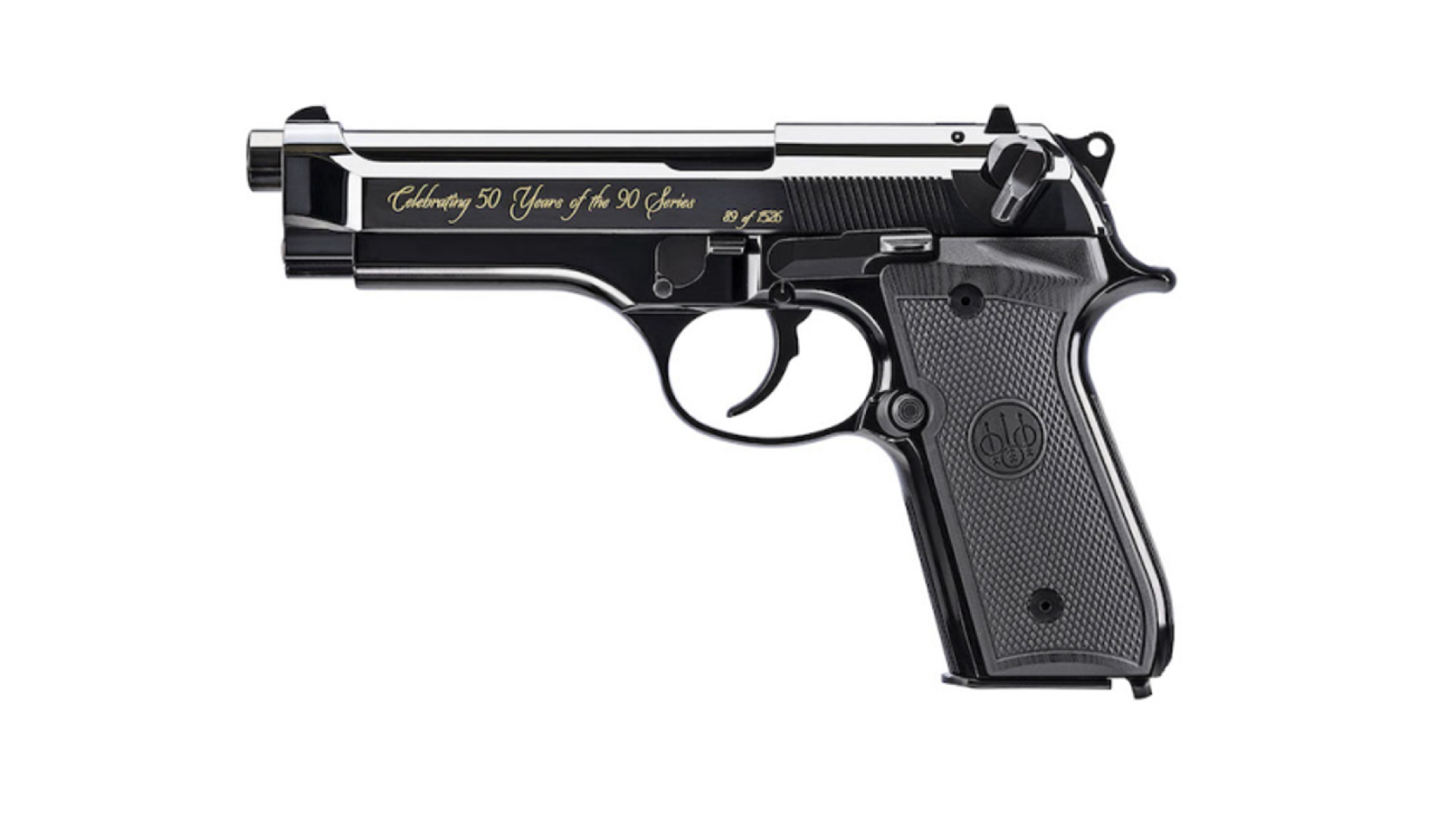

The hunters’ firearm of choice was the 16-lb., single-shot, 34” octagonal-barreled .50-caliber Sharps Old Reliable buffalo rifle. Known as the “Big Fifty,” hunters often used a pair of the guns, alternating shots between the two rifles so as to not allow the barrels to get too hot and become fouled by black powder residue.

It was against these groups of market hunters, numbering in the thousands on the Great Plains, that George Bird Grinnell took his stand in a heroic attempt to save the buffalo from extinction. But time was short. Between 1868 and 1881 commercial hunters had already killed 31 million buffalo. Only a few small herds remained in out-of-the-way places.

Grinnell was not alone in his Quixotic quest. Partnering with him was a young fellow sportsman and hunter, a federal Civil Service Commissioner who would one day rise to the pinnacle of political power to become the 26th president of the United States: Theodore Roosevelt. It was in late 1887 that Roosevelt hosted a dinner party, inviting not only his friend Grinnell but many other prominent sport hunters as well. Together that evening, those men took the initiative of forming the prestigious Boone and Crockett Club, a hunting and wildlife conservation organization that is active and influential yet today.

Of that gathering, author Michael Punke in his 2007 book titled Last Stand: George Bird Grinnell, the Battle to Save the Buffalo, and the Birth of the New West wrote, “February 29, 1888, was a seminal moment in the history of conservation: the first official meeting of the first-ever organization to be formed with the explicit purpose of affecting national legislation on the environment.”

Thanks to the efforts of George Bird Grinnell, Theodore Roosevelt, the Boone and Crockett Club and many other individuals and organizations, the buffalo—America’s Bison—was ultimately saved from extinction, but just barely. It is estimated that less than 1,000 buffalo remained by the time the shooting was stopped. (Some sources say just a few hundred.) Fortunately, today, buffalo are thriving, once again roaming many areas of the Great Plains.

In 1925, while honoring George Bird Grinnell for his efforts not only to preserve the buffalo but also for his tireless work concerning the formation of America’s earliest national parks, President Calvin Coolidge said, “Few have done so much as you. None has done more to preserve vast areas of picturesque wilderness for the eyes of posterity in the simple majesty in which you and your fellow pioneers first beheld them.”

Grinnell Glacier at Glacier National Park is named for George Bird Grinnell.