Mexican-American War, Battle of San Pasqual, Dec. 1846

Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny had been ordered to seize New Mexico and California from the Mexicans. New Mexico had been easy-California, not so much. Kearny had arrived in California with just 100 travel-weary men. Now they were surrounded and outnumbered by Andres Pico and his well-armed troops. To make matters worse, their gunpowder had gotten wet during the trip, so firing their carbines and pistols was a problem, and they were almost out of food and water, too.

If they didn't die at the hands of Pico's men, thought their scout Kit Carson, they'd likely starve to death. It was time to do something-which is how Carson, Ed Beale and the Indian found themselves creeping through enemy lines in the dead of night. Their aim was to reach San Diego-some 25 miles away-and summon reinforcements.

Clank! Beale reached down quickly to silence the rattle of his canteen. Had they been heard? Five minutes passed, then 10, and there was no activity from Pico's men. Carson breathed a sigh of relief. Silently he unclipped his canteen and set in on the ground, motioning the others to do likewise. Crack! His boot came down on a twig. Carson reached for his boots. He pulled off one, then the other before folding the tops into his belt loop. Beale followed suit. Barefoot would be quieter for now. The three men made their way cautiously through the night, keeping to the relatively clear trail as much as possible to avoid making any noise.

By morning they'd made it across enemy lines and were walking through miles of desert, rock and cactus. “Uhh,” groaned Carson as yet another stone tore into his unprotected and now-bloodied feet. Somewhere during the night both he and Beale had lost their boots, making the trek to San Diego a long and painful one.

But make it they did, and two nights later, Carson arrived back at Kearney's hilltop retreat with 200 American troops on horseback-enough force to drive off Pico's army and allow Kearny and his men to continue their mission.

*****************************************************

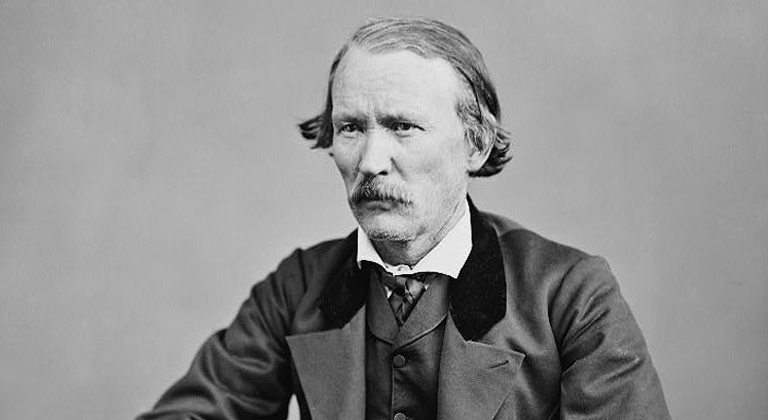

Christopher “Kit” Carson was a man of many talents. Over the course of his life he worked as a trapper, a scout, an explorer, an Indian agent, a soldier and a rancher. Along the way, he became something of a legend.

The Early Years

Carson was born in Kentucky on Christmas Eve 1809 and spent his early childhood in Missouri. His father was killed in an accident when young Kit was just nine years old, at which point Carson dropped out of school to work on the family farm.

At age 14, his mother apprenticed him to a saddle maker, but saddle making wasn't for him. At 16, Carson ran off to join a wagon train heading to Sante Fe, N.M.

Shortly thereafter, he began learning the fur trade from trapper and explorer Matthew Kinkead, a friend of Carson's late father. He also had a knack for languages, becoming fluent in Spanish and several American Indian dialects. Being able to talk with his customers in their own language undoubtedly contributed to his success as a trapper.

Changes of Direction

By 1840 a depression, changing fashions and an over-trapped beaver population caused a decline in income. So when Carson met John C. Fremont, he jumped at the chance to become a guide on Fremont's expedition to map and describe Western trails for the Army. The two made a good team.

Fremont, in turn, wrote reports about his expeditions and about Carson's contributions. During the second expedition, for instance, the group became snowbound, and food was in such short supply that the mules actually ate each other's tails and the leather on the packsaddles. It was Carson's wilderness skills that saved the men from mass starvation.

On that same year-long expedition, Fremont and his party happened upon a Mexican man and boy who were the only survivors of a brutal ambush by a band of Native Americans. Carson and Alex Godey, another mountain man, tracked the ambushers for two days. There, they rushed the encampment, killing two warriors and scattering the rest. Carson and Godey returned to the Mexicans with their horses. Soon Carson was being hailed as a national hero.

The Mexican-American War brought more change to Carson's life when he became a scout for the U.S. Army. He would later serve as a courier, taking messages back and forth between Fremont, by then Governor of California, and the White House in Washington, D.C. At war's end, Carson returned to New Mexico with his family to become a rancher and farmer.