For three years, from 1989 to 1992, Ohio sportsmen were being targeted by a serial killer. During that period, no fewer than five sportsmen were murdered in the field: two while hunting, two while fishing and one who was just out for a walk.

It all began on April 1, 1989, when Donald Welling, age 35, was shot and killed while strolling near his rural home near Strasburg, Ohio, in Tuscarawas County. Two years later, in 1990, the killer struck again. Jamie Paxton, age 21, of Bannock, Ohio, was shot and killed on November 10 while deer archery hunting in Belmont County. Just 18 days later, Kevin Loring, age 30, of Duxbury, Massachusetts, was shot and killed while deer hunting in Muskingum County.

All was quiet for the next two years, until 1992. Then, on March 14, Claude Hawkins, age 49, of Mansfield, Ohio, was shot and killed while fishing in Coshocton County at Wills Creek Dam. Less than a month later on April 5, Gary Bradley, age 44, of Williamstown, West Virginia, was killed while fishing in Noble County. A sixth man, Larry Oller of Barnhill, Ohio, was also shot at while hunting, but escaped unharmed.

Despite an intense investigation, law enforcement offers were at a loss as to who was stalking and killing outdoorsmen in cold blood and why. What the investigators suspected was that the shooter was driving rural roads in the eastern and southeastern portions of the Buckeye State and looking for individuals who were alone, which made hunters and fishermen prime targets. The sportsmen were then shot with a high-powered rifle and left in the field to die.

A multi-agency task force made up of local law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) took to the case. Jerry Wade, a veteran Ohio wildlife officer and field supervisor, represented the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife, on the task force.

“At first we thought that possibly an anti-hunting extremist was to blame for the killings,” said Wade. “But that theory was eventually ruled out. The FBI developed a profile of the suspect we were looking for, and an anti-hunting extremist just didn’t fit the profile.”

Officers got a break in the case when, in early November 1991, a chilling letter was sent by the killer to a Martins Ferry, Ohio, newspaper editor. The letter linked the five killings, and was received close to the anniversary of the death of the second victim, Jamie Paxton. It read, in part:

“…the motive for the murder was this—the murder itself. With no motive, no weapon, and no witnesses you could not possibly solve this crime. Paxton was killed because of an irresistible compulsion that has taken over my life. I knew when I left my house that day someone would die by my hand. I just didn’t know who or where.”

The letter continued, “…five minutes after I shot Paxton I was drinking a beer and had blocked all thoughts of what I had just done out of my mind. I thought no more of shooting Paxton than shooting a bottle at the dump.”

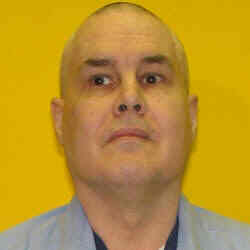

Gradually, the law enforcement task force developed a list of suspects, and on it was Thomas Lee Dillon, who was living in northeast Ohio with his wife and son. But authorities had little evidence tying Dillon to the crimes, so they appealed to the public for help.

A tip eventually came in from a confidential informant who claimed he had gone deer hunting with Dillon two years earlier. He said Dillon had hunted with a type of rifle that was illegal for hunting use in Ohio at the time—and that Dillon had killed a doe. He also said that he knew where Dillon had been standing when he shot the doe, and that he (the informant) had seen two empty shell casings on the ground. Officer Wade asked the informant to take him back to the scene.

“I remember it was a cold November day and the weather was lousy,” Wade said, “a mixture of snow, rain, and wind. And to make matters even worse, the fencerow where Dillon had supposedly been standing when he shot the doe had been bulldozed. It was gone. The informant tried to remember the best he could where he had seen the two rifle shell casings, but I knew finding them would be a long shot.”

Officer Wade spent the next several hours slowly going back and forth over the area, searching the ground with a metal detector. “I finally got a faint hit,” he said. “It wasn’t an audible beep from the metal detector; the needle on the gauge just moved slightly. So I marked that spot and kept searching. Finding nothing else, I returned to my mark, dug down about an inch and a half, and found one of the shell casings. I soon found the other casing about 20 to 30 feet away.”

Wade gave the two shell casings to the FBI, and they were able to match one of them to the rifle—a 6.5X55mm Swedish Mauser—used in the killings of Gary Bradley and Claude Hawkins. That key piece of evidence helped link Thomas Lee Dillon to the rifle in question, and he was subsequently charged in January 1993 with the two murders.

Wade gave the two shell casings to the FBI, and they were able to match one of them to the rifle—a 6.5X55mm Swedish Mauser—used in the killings of Gary Bradley and Claude Hawkins. That key piece of evidence helped link Thomas Lee Dillon to the rifle in question, and he was subsequently charged in January 1993 with the two murders.

In a plea agreement, Dillon confessed to all five sportsmen murders, plus numerous vandalism and arson charges. He was convicted and sentenced to five consecutive terms of 30 years to life for aggravated murder. Thomas Lee Dillon died in prison in 2011 at the age of 61.

In an ironic twist to this case, Dillon had an encounter with a state wildlife officer two months prior to his arrest. Officer Tim Jordon observed Dillon illegally target practicing on a state wildlife area, using a handgun with an illegal silencer attached. As a result, the federal Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) charged Dillon with possession of the illegal silencer. During his pre-sentence investigation through the federal court system, the task force had Dillon under surveillance, which in turn led to his arrest for the sportsmen murders.

In 1993, Jerry Wade received two awards for his role in capturing Dillon.