How different might American history have been if Abraham Lincoln, at age 33, had been shot and killed in a duel? It almost happened. On September 22, 1842, our future 16th president, at the time an Illinois state legislator, met to duel with state auditor James Shields. Thankfully, their “seconds” intervened and persuaded the two against it.

And Lincoln was not the only famous American of his time to come perilously close to involving himself in a deadly duel. In 1864, a young newspaper reporter by the name of Samuel Clemens—one day to be known as Mark Twain—was challenged to a duel by a rival newspaper editor. But as with Lincoln, Clemens’ second intervened, exaggerating Clemens’ skill with a pistol and ending the challenge.

Dueling was common in Europe for centuries, mainly with swords, before being imported to America where pistols became the weapon of choice. Duels were fought to settle a disagreement over so-called honor, a real or perceived snub. And the goal was not so much to kill an opponent as to gain “satisfaction.” In other words, to restore a person’s honor by demonstrating his willingness to risk his life. Mainly men of the upper classes participated in duels, but a few women as well were occasionally known to settle their differences by shooting it out.

A duel was a very formal affair, with the offended party sending a written challenge to the person who had wronged him. The challenged person then had the option of either accepting or rejecting the challenge. If accepted, the two men’s friends, known as seconds, would work out the details of the duel—where, when, etc.—at times even debating the expected dress code and whether or not refreshments would be served.

The person challenged was usually entitled to choose the weapons. As previously stated, pistols were most often used in America, but in Europe anything was fair game, from swords to sausages. Yep, you read that right. Sausages.

In the 1860s, Otto von Bismarck, the future Chancellor of the German Empire from 1871 to 1890, was reported to have challenged a man to a duel who chose as the weapons two pork sausages, one of which was to be infected with the roundworm Trichinella. Each man would eat a sausage and wait to see what happened. Bismarck decided he didn’t have the stomach for such a challenge and declined.

Other oddball European duels included two Frenchman, who in 1808, were said to have dueled over Paris from hot-air balloons. They fired at each other with pistols, attempting to puncture the other man’s balloon. One of the men was supposedly shot down, dying along with his second. In 1843, two other Frenchmen dueled by throwing billiard balls at one another.

In early America, dueling pistols were usually a matched pair of single-shot flintlock or percussion-cap weapons, firing a lead ball at about 830 feet per second. Common calibers included .45, .52, .58 and .65. Propelled by black powder, such a round was equivalent in lethality to today’s .45 ACP cartridge. The guns’ barrels, usually about 10 inches long, were sometimes rifled and sometimes not. With the distance of most duels being only about 35 to 45 feet between participants, the pistols did not need to be extremely accurate.

Dueling became quite common in America during the 19th Century. Between 1798 and the start of the Civil War (1861-1865), the U.S. Navy is said to have lost two-thirds as many officers to dueling as it did to combat at sea. The custom was particularly popular for settling political feuds. The most famous confrontation occurred in 1804 when the sitting Vice-President of the United States, Aaron Burr, shot and killed his political rival, the former U. S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

The Burr-Hamilton duel took place along the banks of the Hudson River, the particular location—the cliffs below Weehawken—chosen for its isolation and jurisdictional ambiguity. Dueling was illegal, and no one seemed to know for sure whether New York or New Jersey laws applied in that area. River islands between two jurisdictions were also popular dueling grounds.

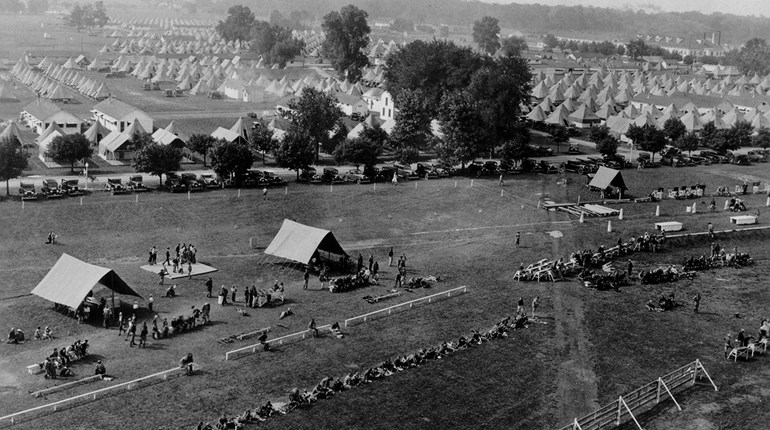

Duels traditionally took place at dawn. The seconds would carefully stake out the grounds, making sure that neither man had an advantage. A sword was thrust into the ground where each combatant was to stand. And then, at a prescribed signal, usually the drop of a handkerchief, the duelists were free to engage.

Each person fired one shot. If no one was hit, up to two more volleys might ensue, but to have more than three exchanges of gunfire was considered barbaric. Although, not everyone held to such rules. A story is told of one duelist who asked his opponent how many shots were to be fired. The other man replied, “Just as often as your Lordship pleases; for I have brought a bag of bullets and a flask of gunpowder.” Obviously, it wasn’t considered poor form to try and get into your opponent’s head.

Dueling in America gradually faded following the Civil War. But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in France, ritualized pistol dueling actually became a sport.

The two combatants were each armed with a conventional pistol, but cartridges were loaded only with wax bullets and no gunpowder. The bullets were propelled by the cartridge’s primer. Participants also wore heavy clothing for protection and a metal helmet with a glass eye shield.

As late as 1908, pistol dueling was an associate (non-medal) event at the Summer Olympics in London, England. Dueling, with swords, persists yet today at the modern Summer Olympics held every four years, and medals are awarded. The event is called Fencing.