Less than a century ago, there were so many elephants in some regions of Africa that they had literally become a nuisance and danger to local human populations. For instance, in Mozambique on the east coast of Africa, elephants were so thick that they were causing extensive crop damage, resulting in African villagers not only starving but being killed by rogue elephants. As a result, the government declared an open season on elephants in 1937, and a young man named Wally Johnson was there to take advantage of the problem pachyderm population.

Becoming a hunter while yet a teenager, Johnson went on to build a career as one of the premier professional hunters in Africa during the mid-20th century, guiding safaris for more than 50 years. During those years he had many scrapes with death, including surviving the bite of a deadly Gaboon viper and being gored by a buffalo. In addition, he and his safari clients—including the writer Robert Ruark and the Michigan bowhunter Fred Bear—were charged many times by Africa’s “Big Five” most dangerous game animals: elephant, lion, leopard, Cape buffalo and rhino.

Walter Walker Johnson was born in 1912, but he was never quite sure exactly where. All he knew was that his parents were aboard a ship when he was born, somewhere between Australia and Durban, South Africa. When asked if he remembered the name of the ship, Wally quipped, “I don’t recall. I was just a little baby, you know.”

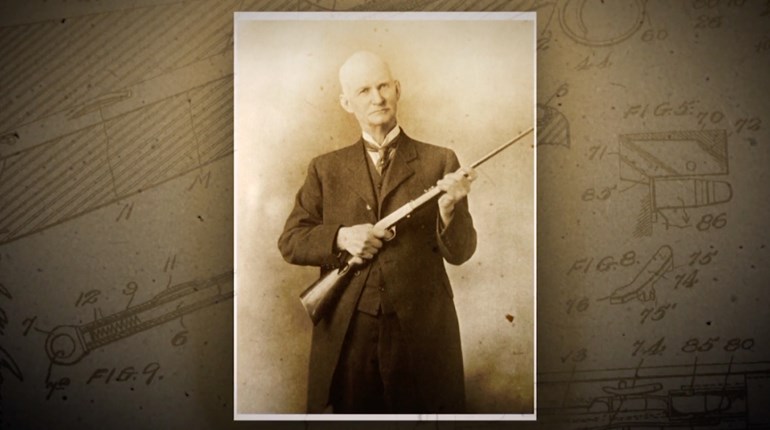

Wally left school at age 14 to join his brother-in-law as a shipping clerk in the Portuguese port town of Lourenco Marques. A truly unspoiled part of the world at the time, wild game teemed at the edge of town and African hunting adventures beckoned. But Wally might have spent his entire career as a shipping clerk had his brother-in-law not bought a battered .303 British Lee-Metford rifle for him. That old gun changed Wally’s life.

Johnson estimates that at the end of his hunting career he had taken an astounding 1,300 bull elephants. In addition, he had also killed some 300 cow elephants, in self-defense, as they charged him or a client. In justifying killing that many tuskers he said the following:

“I must explain to those who didn’t know Mozambique in 1937, and who probably have a very different perception today of the problem, that people were dying by the hundreds because of the depredations of the elephants. It was absolutely pathetic. I was there to see it. Elephants had been protected and had grown so in numbers that they actually started taking over whole areas of cultivation. People were literally starving to death because the elephants had eaten their fields before they could harvest them. It was truly a catastrophe. It was elephants or people. Period.”

Johnson also stressed that the elephants weren’t simply shot and wasted. The ivory was harvested and sold—which was legal at the time—and the meat was either eaten fresh or dried for later consumption, the dried meat known as biltong.

“Now, we never wasted the meat from such hunts, but would dry it in the dry season, when it was a bonus for the men working for me. It was a form of currency. ‘Meat for meat,’ as the Africans put it.”

Not only were elephants numerous, but the size of the tusks on some of the older, bigger bulls was stupendous, rarely seen today. For instance, anything weighing 100 pounds or more per tusk was considered a trophy. Johnson’s best bull ever had tusks weighing 160 pounds per side, a total of 320 pounds of ivory on just one elephant.

But simply because elephants were numerous did not make them easy to hunt. “Elephant hunting is one of the hardest jobs in the world,” said Johnson. “You walk all day, finally come up to an elephant, the b______ gets your scent, and it’s off. Way off! Sometimes you follow two or three days; no food, no water. So you drink anything you can find in the bush. Then you get up to the herd and again the buggers get your scent. It’s two days back to camp, and soon you are repeating the same performance.”

There were no four-wheel-drive vehicles in those days, so Johnson thought nothing of parking his safari truck and walking 60 to 70 miles during a two-day hunt. He said that sometimes hiking 200 miles on an extended hunt seeking elephants was not out of the ordinary.

Strange things sometimes happen on safari; some so strange they are inexplicable. Such was the case in 1955 with the disappearance of one of Wally Johnson’s trackers and gunbearers, Florinda. Johnson was hunting buffalo and had taken with him his head gunbearer and tracker, Luis, a couple of other men to cut up the meat and Florinda.

“I had an extra 9.3mm Mauser rifle, which I lent to Florinda as he … could shoot quite well. I figured he might be able to kill one buff while I shot the other.”

The group of hunters was crawling through thick brush when Florinda tapped Johnson on the shoulder and pointed. Not 20 yards away was a small group of buffalo, including one very large bull standing off to the side. The wind was in the hunters’ favor and the buffalo had not yet scented them, so Johnson took careful aim with his .375-caliber magnum rifle and dropped the bull in its tracks with a spine shot.

The rest of the herd thundered off, but when the men walked up to the downed bull Florinda was nowhere to be seen. Was he following the remainder of the herd? It wasn’t long before they heard a single shot in the distance, and figured that, yes, Florinda had indeed killed a second buffalo and would soon meet them back at camp. But Florinda did not show up at camp, not that night, nor at sunrise the next morning.

Now truly worried, Johnson and the others returned to the site of the previous day’s hunt and tracked Florinda some distance to where they eventually found blood. Whether it was human blood or animal blood they couldn’t tell; unfortunately, the tracks faded from there. They searched the area for four long days but found no sign of Florinda: no rifle, no clothing, no boots, no nothing.

Florinda was never heard from again, and the borrowed rifle he was carrying was never recovered. It is believed he died tragically in the bush, but it will never be known exactly how or why. The incident haunted Wally Johnson for the rest of his life.

“Looking back now, with the perspective that only age can bring, there are indeed some experiences I wish I had never had to endure, and there are incidents I wish I could have handled differently. But, given the choice, I would live my life again as a professional hunter in Africa where my home was the bush and my days were filled with adventure.”

If you’d like to read more about Wally Johnson’s many African hunting adventures, the book The Last Ivory Hunter: The Saga of Wally Johnson is highly recommended. Written by author Peter Hathaway Capstick, for years a professional African safari guide himself, he captures perfectly life on the Dark Continent as it once was ... but will never be again.