Five days before Christmas in 1943, over the worn-torn skies of Germany, an unlikely incident occurred between two enemy aircraft that was so improbable, so unbelievable, that the event would become known as “the most incredible encounter between enemies in World War II.”

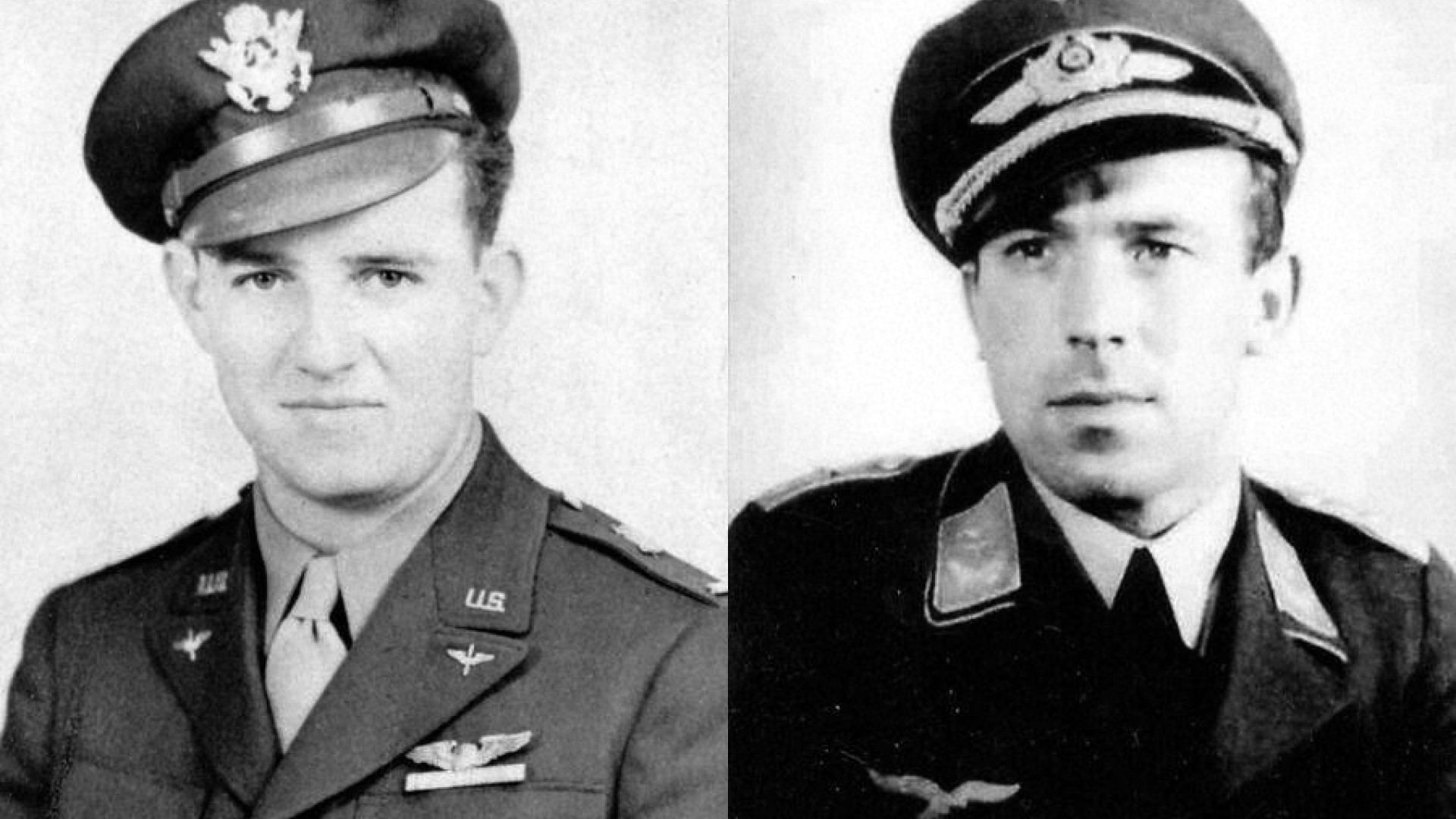

Piloting an American B-17 bomber that day was Second Lieutenant Charles L. “Charlie” Brown, just 21 years old. A former West Virginia farm boy, Brown and his crew of 10 airmen had been in training for months, and were now flying their very first combat bombing mission over enemy territory.

Also in the sky that day was another second lieutenant, Franz Stigler; but he, unlike Brown, was no rookie. Flying a fast, sleek German Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter, Stigler was an ace ... in fact, he needed to shoot down just one more Allied bomber to earn the coveted Knight’s Cross.

Lieutenant Brown and his untried crew had heard the stories of veteran American pilots—how war was hell and that many planes did not return from their mission—but now they were experiencing the terrors of air combat firsthand. Flak, antiaircraft 88mm shells fired from the ground, burst around their B-17 (nicknamed Ye Olde Pub), the concussion and shrapnel of the exploding shells rocking their plane.

“We’re hit!” screamed one of the crewmen. “We’re hit in the nose, there’s a big hole!”

Flak had sheared off a large portion of the bomber’s Plexiglas front, allowing a 200-mile-per-hour, sub-zero-temperature wind to pour through the jagged hole. In addition, engine number two had also been hit, was smoking, and had to be shut down. And that was not all: The co-pilot reported that a shell had passed completely through the right wing. “It didn’t explode,” he yelled to his captain, “but we got a helluva hole!”

Brown and his crew swallowed hard, persevered, and within a few minutes dropped their bomb payload over the intended target, an aircraft manufacturing plant far below. But then, turning for home, they soon faced another danger, a dozen or more German fighter planes blocking their path.

The fighters didn’t hesitate. Diving quickly to the attack, their blazing machine guns and 20mm cannons chewed off half of the bomber’s rudder and most of its left horizontal stabilizer wing. The B-17’s machine gunners desperately returned fire . . . until their .50-caliber guns either ran out of ammunition or froze and stopped working altogether due to the severe cold. The bomber was now not only barely able to stay in the air, it was also defenseless.

Sensing the bomber’s vulnerability, the German fighters swarmed to the kill like a school of sharks. Firing at nearly point-blank range, they poured fire into the plane, killing one of its crew members, severely wounding others, and knocking the bomber into a death spin. The spiral quickly turned into a nose dive, the bomber plunging nearly 5 miles straight down. The plane was less than 2,000 feet from slamming into the ground when Charlie Brown was able to pull the nose up and level off, a miraculous exhibition of flying skill. However, now forced to fly low and slow, just above stall speed, the crippled B-17 was a sitting duck.

Franz Stigler, who had landed at a nearby airfield to refuel, couldn’t believe his good luck when he looked up and saw the bomber lumber overhead, barely higher than the treetops. Within minutes, he was back in the air, ready to finish off Ye Olde Pub and claim his Knight’s Cross.

Those members of the bomber’s crew still in the fight saw the single fighter rapidly approaching from behind but could do nothing to stop it. They merely tracked the German plane with their useless guns as a bluff. Stigler closed to within 100 yards of the severely damaged plane and had his finger on the trigger of his machine guns, ready to fire, when he sensed something was not right.

Moving his fighter closer, he surveyed the extensive damage and marveled that the bomber was still somehow flying. Edging even closer, he was able to make out the frightened faces of some of its crew huddled inside, staring back at him.

It was at that moment that Second Lieutenant Franz Stigler had a change of heart. His older brother, August, had been a bomber pilot and was killed earlier in the war, shot down. It was because of his brother’s death that Franz had volunteered for fighter duty, to avenge August’s death. He now thought of his brother and how much he missed him, and he realized that the family members of these men would miss them just as keenly. But he also struggled with the fact that it was his duty to shoot down enemy aircraft. He could be court-martialed for not doing so, and would probably face a firing squad as a result. But, somehow, at least in this instance, he simply could not bring himself to pull the trigger.

“This will be no victory for me,” he finally decided. “I will not have this on my conscience for the rest of my life.”

Stigler maneuvered his fighter even with the right wing of the bomber until he could clearly see Charlie Brown hunched behind the controls. Waving to get the American pilot’s attention, Brown stared straight ahead. When Brown finally glanced to his right, he got the shock of a lifetime. “I looked out and there’s the world’s worst nightmare sitting on my wing,” Charlie would remember.

Stigler then nodded at Charlie, and with his left hand pointed toward the ground, motioning for Charlie to land in Germany. Charlie shook his head no.

The two planes were quickly approaching the German coastline, where both pilots knew that flak guns would soon open up again on the bomber and take her down. But would the flak gunners hold their fire if they saw a German plane accompanying an American B-17?

Stigler decided to take that chance. He held his breath and escorted the bomber over the coast. No flak guns erupted. The two planes were flying so low that they could see the confused looks on the soldiers’ faces below, but yet the gunners held their fire.

Once over the North Sea, Stigler again tried to communicate with Charlie using hand signals. He pointed to the east and repeatedly mouthed the word “Sweden,” knowing that Sweden, a neutral country during the war, was just a half-hour flight away, and that Charlie’s crew could get the medical help it needed there. England, on the other hand, was two hours away, and Stigler seriously doubted the badly shot up B-17 could make it that far.

Neither Charlie nor his co-pilot understood what the German pilot was suggesting. Frustrated, Stigler finally saluted and turned his fighter back toward Germany, thinking to himself, “Good luck, you’re in God’s hands now.”

Miraculously, later that day, Charlie Brown and his aircrew did return to England, but just barely.

Both pilots, Brown and Stigler, survived the war. Charlie flew 28 missions, with Franz logging nearly 500. As they both grew older, neither man forgot that incident in the sky over Germany and often wondered about it. Would they possibly somehow, someday, make contact with one another once again? Forty years later, Brown was able to track down Stigler through a wartime pilots’ organization, and the two men agreed to meet. Both were apprehensive, but it turned out to be an emotional, tearful reunion.

Charlie’s wife, Jackie, asked him when he returned home, “Well, did you find out why he spared you?”

“Yes,” Charlie smiled. “I was too stupid to surrender, and Franz Stigler was too much of a gentleman to destroy us.”

Stigler wrote of their meeting, “In 1940, I lost my only brother…On the 20th of December 1943…I had the chance to save a B-17 from her destruction, a plane so badly damaged it was a wonder she was still flying. The pilot, Charlie Brown, is for me, as precious as my brother was.”

If you’d like to read more about this amazing World War II story of chivalry amidst the horrors of war, the book A Higher Call by Adam Makos is highly recommended.