Squeezing the trigger is the essence of every shot. Do it right, and you succeed. Do it wrong, and no matter how good everything else was—breath control, grip, stance, sight picture—the shot will not find its mark.

You may think pulling the trigger is no more than a small contraction of the muscles of the index finger. But in fact there’s much more involved: technique, trigger mechanisms, mental tasks and psychology.

Trigger Technique

The trigger hand is a key contact point between the shooter and the gun’s stock. It plays an important part in supporting and steadying, and yet its main function is to place the trigger finger in the ideal position. The grip must be the same for every shot—same placement, with the same firmness. The finger must be placed on the trigger in the correct location, and its movement must be directly in line with the barrel and the line of fire, shot after shot. That movement must be deliberate and controlled.

It would seem that what we require in a good trigger pull should be quite simple—just a small flexing of the finger followed by a careful squeeze. But it’s deceptive because it depends being consistent, in a precise direction, accurately applied and perceived, and being decisive.

Trigger Configuration

The link between the finger and the actual shot is the trigger mechanism itself.

Think of the trigger as a simple mechanical lever. The resistance that must be overcome to fire the shot depends in part on where the finger is placed on the trigger. Placing the finger high increases the necessary pressure, while placing the finger low will increase the lever’s mechanical advantage and make the trigger feel lighter. Thus the shooter must always place the finger in exactly the same spot to get a consistent feeling.

Trigger width can also change the way one trigger feels versus another. A wide trigger spreads pressure over a larger area, making it feel like it takes less force to fire the shot. One of the risks with wide triggers is that more pressure may be applied to one side or the other, thus causing lateral displacement of the gun.

Another factor is curvature. Curved triggers can help the shooter place the finger in the middle of the trigger. Straight triggers may have a small clip or marking point that can help the shooter place the finger on the same spot for each shot. The triggers on many firearms are adjustable and some are replaceable, so you can tailor this key component to what suits you.

Trigger Types

By far the most common type found in both rifles and handguns is the single-stage trigger, where the shooter applies pressure until the full resistance is overcome. Sometimes referred to as a “direct” trigger, since movement after the finger contacts the trigger releases the shot, they come as standard equipment on most firearms and are universally preferred in situations where quick shots may be required, such as personal protection and hunting. Movement required to break the shot is called “creep,” and an excessive amount of it can frustrate accurate shooting and must be remedied through diligent practice or mechanical improvement of the mechanism.

Some shooters have problems initially learning how much pressure can be applied to single-stage triggers, especially those set to a light pull weight. Such cases reinforce how critically important it is to ALWAYS keep the gun pointed in a safe direction, and if there’s ever concern with the operation of a particular trigger, that gun should examined by a qualified gunsmith before continued use. With sufficient practice, however, virtually any shooter can get accustomed to engaging and operating a given trigger with the proper amount of tension.

Precision rifles often come with two-stage triggers. These have a certain amount of movement or travel that must be taken up before a second stage is reached. When the second stage’s resistance is overcome, the shot is fired. There are some characteristics common to two-stage triggers:The first stage should not be very long. It should take little time and require minimal change in finger position during movement. It should have the same resistance throughout its travel and never stick or catch before the second stage is reached.

The best triggers will have absolutely no play in the second stage. Shooters call this a “clean break,” or release, of the trigger. Even a small amount of creep (intermediary trigger movement that occurs before releasing the shot) is especially vexing to precision shooters, causing off-call shots, and in their finely tuned guns may be caused by incorrect adjustment or mechanical wear. As a result match competitors and other precision shooters often need to have their triggers adjusted, and in some cases fixed or replaced before they can attain maximum accuracy.

Mind Over Matter

Why is pulling the trigger so difficult sometimes?

Good question. So far we have looked at physical, technical and mechanical aspects of pulling the trigger. Now we consider the mental part—how to pull the trigger at the right time and in the right way to improve your chances of hitting the target.

All the information about the shot—sight picture, movement, muscle tension and trigger pressure—comes together and is processed in the brain. When the decision to shoot is made, it is put into action instantaneously.

The correct decision can occur only when you have received and assessed the relevant information.

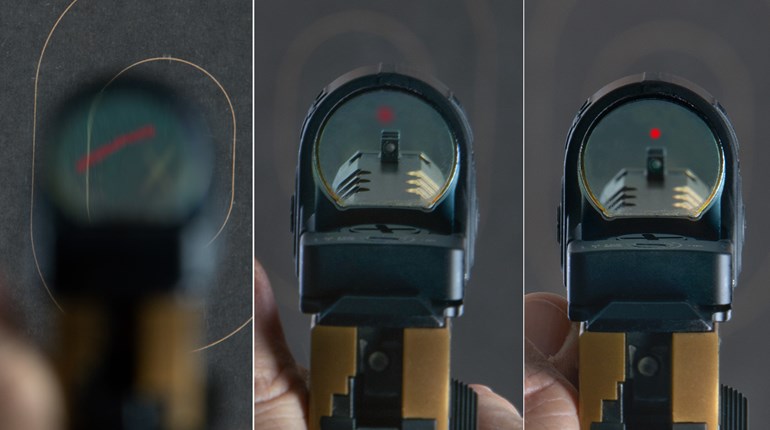

What kind of information is presented to the shooter through his or her senses? First and most obvious, is the sight picture, the position of the front sight or reticle in relation to the target. The shooter can see the errors of the actual picture versus the ideal, as well as the sight’s movement characteristics and speed, what some refer to as the “wobble.”

Only when the wobble is at the absolute minimum and the sight picture is right do you squeeze the trigger. That squeeze must be deliberate, but also gentle, so as not to pull the shot away from the aiming point. Tension on the trigger should be increased incrementally and never impulsively yanked or jerked.

In the final stages of the shot the shooter should be concentrating on decreasing the wobble between the aiming point and his gun’s front sight or reticle. However, no matter how good a shooter is, wobble is never completely eliminated, and so there’s a timing factor in making a successful shot. After extensive practice, when the proximity between the front sight/crosshair and the target is optimal, the shot will seem to fire itself. It takes regular and systematic training to master sight picture and trigger control coordination, and it takes intense concentration to do it right shot after shot.

For successful shooters this often becomes an intuitive process, the byproduct of countless repetitions during practice sessions. These skills form the basis for accurate shooting, and when each step occurs correctly, the shot will be on target.