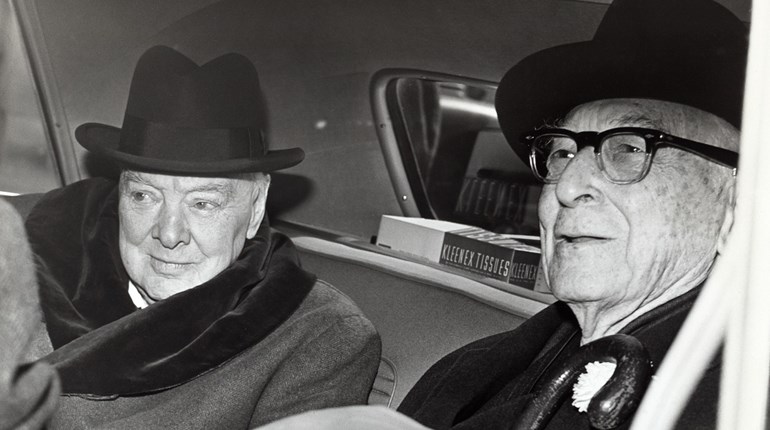

The author of nearly 30 books detailing the secrets of hunting the wild turkey, Tom Kelly of Alabama is the undisputed dean of that particular literary genre. In short, when he speaks, wise turkey hunters listen.

Tom enjoys recommending good books to turkey hunters, and one of his favorites is the classic Illumination in the Flatwoods: A Season Living Among the Wild Turkey, published in 1995. It is not one of Kelly’s many titles and, ironically, the book makes little mention of turkey hunting. Rather, it is a true story of wild turkey behavior, as intimately witnessed by wildlife biologist Joe Hutto.

Hutto had become fascinated with the wild turkey as a boy, through hunting, and dreamed of someday experiencing the world through the eyes of this magnificent gamebird. It was during the late 20th century, while working in northern Florida, that Hutto got his once-in-a-lifetime chance. His neighbor, a farmer, brought him two clutches of wild turkey eggs, explaining to Hutto that the hens which laid them had both been killed in mowing accidents. Consequently, the eggs were not going to hatch unless someone intervened.

Totally unprepared, Hutto scrambled to borrow an incubator from a friend and then set about hatching the two dozen speckled, cream-colored eggs. He dutifully turned them twice each day, as a wild hen would in the nest, making turkey sounds as he did so, producing soft clucks, yelps, and purrs with his mouth. As the young turkeys matured within the eggs, they began answering Hutto. His intent was to familiarize the birds with his voice, hoping they would imprint upon him as their mother when they hatched, and that’s exactly what happened.

Hutto moved the young turkeys, known as poults, from the incubator, to a brooder box, then eventually to a large outdoor pen. In the pen he provided roosts, poultry feed, water and 200 crickets per day that he purchased from a local bait-and-tackle shop. As the birds grew, Hutto began taking them on daily walks throughout his rural property, in essence leading them on foraging expeditions as a hen would. The young birds quickly learned to feed on grasshoppers, spiders, berries, seeds and a multitude of other wild foods.

It was during this early period of the birds’ lives that Hutto began realizing just how much the poults depended upon him for guidance and protection. As a result, he made the difficult decision to temporarily drop out of human society for a time and become a fulltime wild turkey hen. It was a decision that would eventually reveal wild turkey behaviors never before known to wildlife science.

“Had I known what was in store … I would have been hard pressed to justify such an intense involvement,” said Hutto. “But, fortunately, I naively allowed myself to blunder into a two-year commitment that was at once exhausting, often overwhelming, enlightening, and one of the most inspiring and satisfying experiences of my life.”

Several months into the experiment, Hutto wrote in his daily field journal, “I am constantly reminded that these birds have innate knowledge that facilitates the recognition of things previously unknown: the ability to distinguish the silhouette of a soaring hawk from that of a vulture at a thousand feet, recognizing a venomous snake as more dangerous than a nonpoisonous one; complete insect recognition regarding palatability and danger. All of these attributes are manifest almost from birth with no need of trial and error. The turkeys just already know. It is the specificity of this knowledge that is so remarkable.”

During their frequent forays, the turkeys (including Hutto) were constantly on alert for predators, particularly from overhead. Hutto soon learned three levels of vocalizations from the flock regarding distant soaring aerial predators.

“The first level of caution is represented by a lazy nasal whine, which serves to gain everyone’s attention but is not alarming,” he said. “Next, an ascending purr will bring about various cautionary behaviors like freezing or squatting, and frequently serves as a signal to assemble and be still. If danger seems imminent, this signal will cause the turkeys to dive under the cover of a nearby bush. All of this is dependent on the inflection of the purr and the accompanying visual stimulus—hawk, kite, vulture, et cetera. All of which they seem to be able to differentiate. A raptor in straight flight is always more disturbing than one that is soaring. After the turkeys have reacted to the alarm and are motionless, a low, breathy, voiceless hiss will bring about absolute silence and stillness for several minutes or until the hawk is out of sight.”

Although Illumination in the Flatwoods is not a treatise on turkey hunting, Hutto does include a few tips for hunters.

“That wild turkeys are clever and wily is a cliché among hunters and people who have had any experience with them. No one comes to terms with this phenomenon more than the turkey hunter. A turkey’s sensory ability clearly borders on the supernatural.

“I am astounded by the wild turkey’s ability to determine distance and direction, and I have learned that a spring gobbler who answers my call from a quarter of a mile away needs no other sound from me. If he chooses to come, he will know almost exactly from what bush or tree the call came. Even through dense terrain, I have had turkeys come on the run from such a distance and stop within twenty yards, then begin examining my exact location for the source of the yelp.

“Vision in wild turkeys, although very accurate, may be no better than human vision. Where wild turkeys excel is in their ability to detect movement. They apparently can discern (in a fully animated world) the smallest movement. A tiny flicker of motion fifty yards away gets their attention like a slap in the face.

“Hearing is acute in wild turkeys, although it is difficult to study. I do find, however, that sounds in general, although never ignored, may be tolerated, provided they do not have dangerous associations. The turkeys are perfectly comfortable with a chainsaw as long as it, like the noisy red-shouldered hawk, remains in the distance. Wild turkeys can be very attentive to camera noises for a short time, but if the photographer is completely concealed, the sounds will eventually be ignored. One sure way to disturb or frighten wild turkeys, ironically, is with a turkey caller. They seem very limited in their tolerance for meaningless yelping.”

If you need even more encouragement to read Illumination in the Flatwoods, Tom Kelly makes it plain. “If you can’t afford to buy the book, borrow it. If you don’t have many friends and have no access to libraries, steal it. But whatever you do, read it.”

By the way, last spring at age 95—and just three weeks from turning 96—Tom Kelly pulled the trigger on yet another gobbler. When Tom Kelly speaks, wise turkey hunters listen.

***

Note: Joe Hutto’s book, Illumination in the Flatwoods, was adapted into a fascinating one-hour documentary film, My Life as a Turkey, by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and can by viewed on YouTube here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENr62-oWyPs&ab_channel=symmetry.